The Deviator

Erasure of the Source

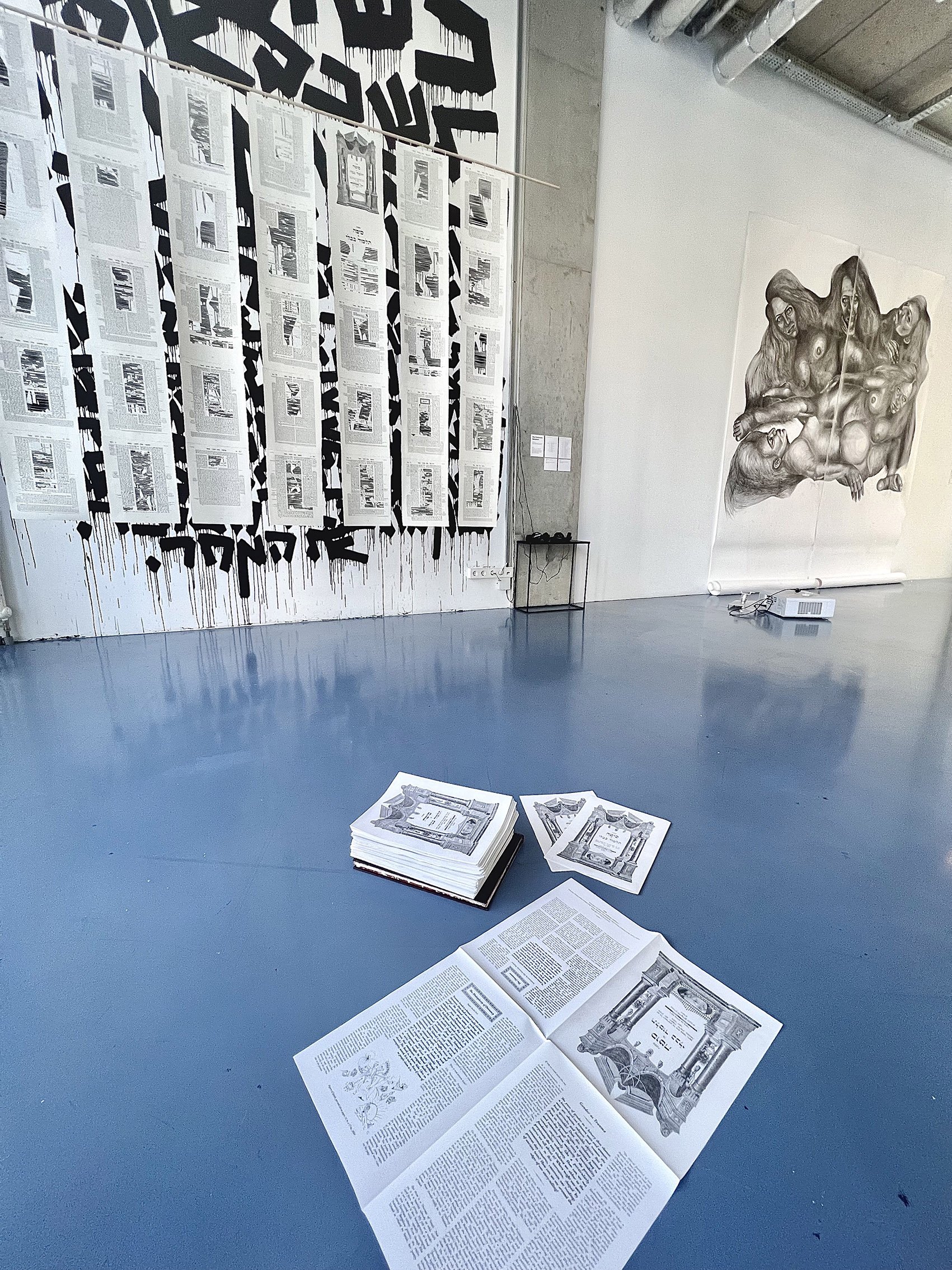

What is the magnitude of impact of Jewish ancient literature on modern Jewish identities worldwide? Exposure of the absence of women and misogynistic tendencies within Rabbinic literature and ritual is achieved in a multi-faceted collaborative installation, incorporating poetry, sculpture, painting, and sound, all elements alluding to the Talmud (500 CE), a foundational text in Jewish cultural life, deeply ingrained in contemporary Jewish thought worldwide.

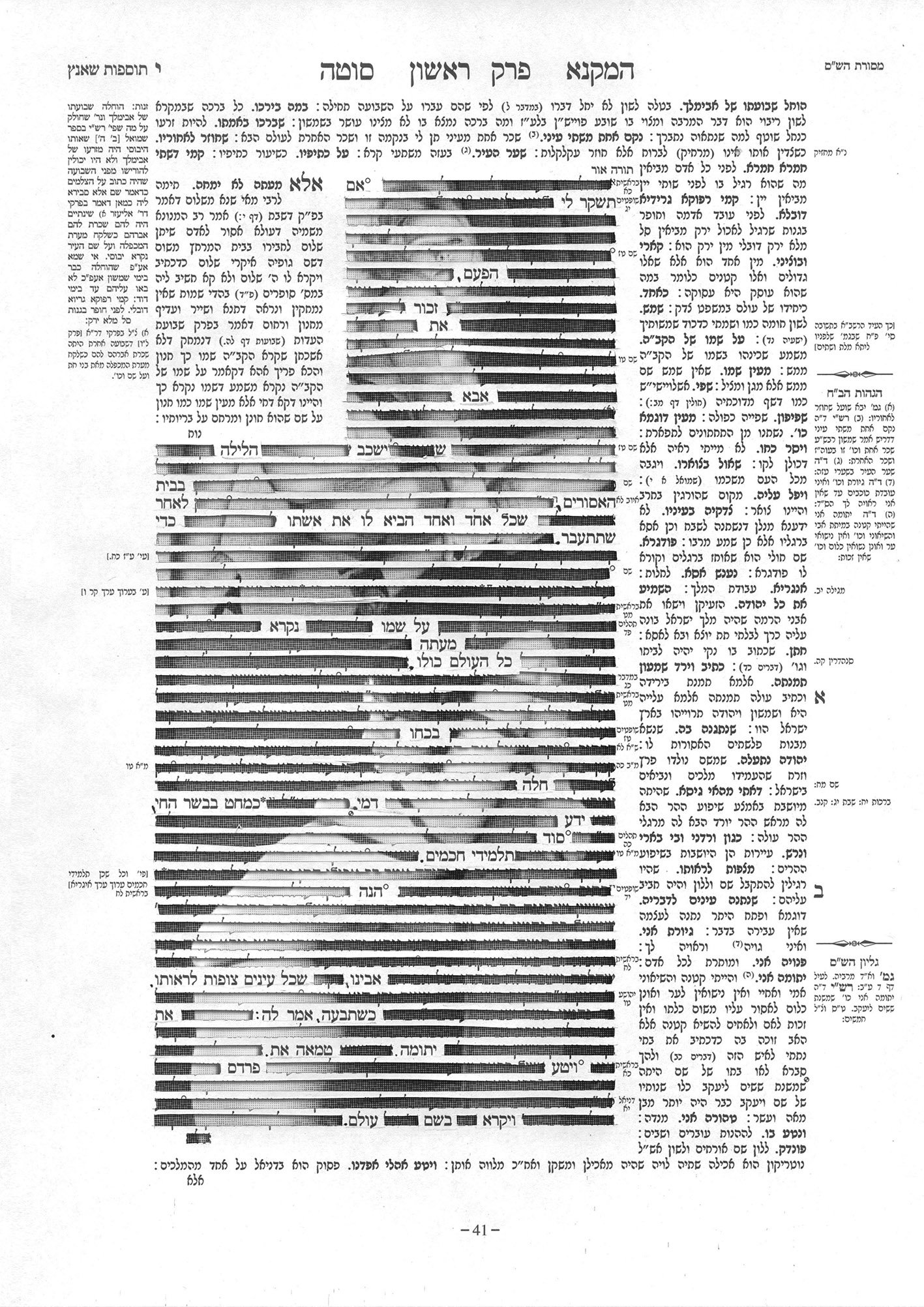

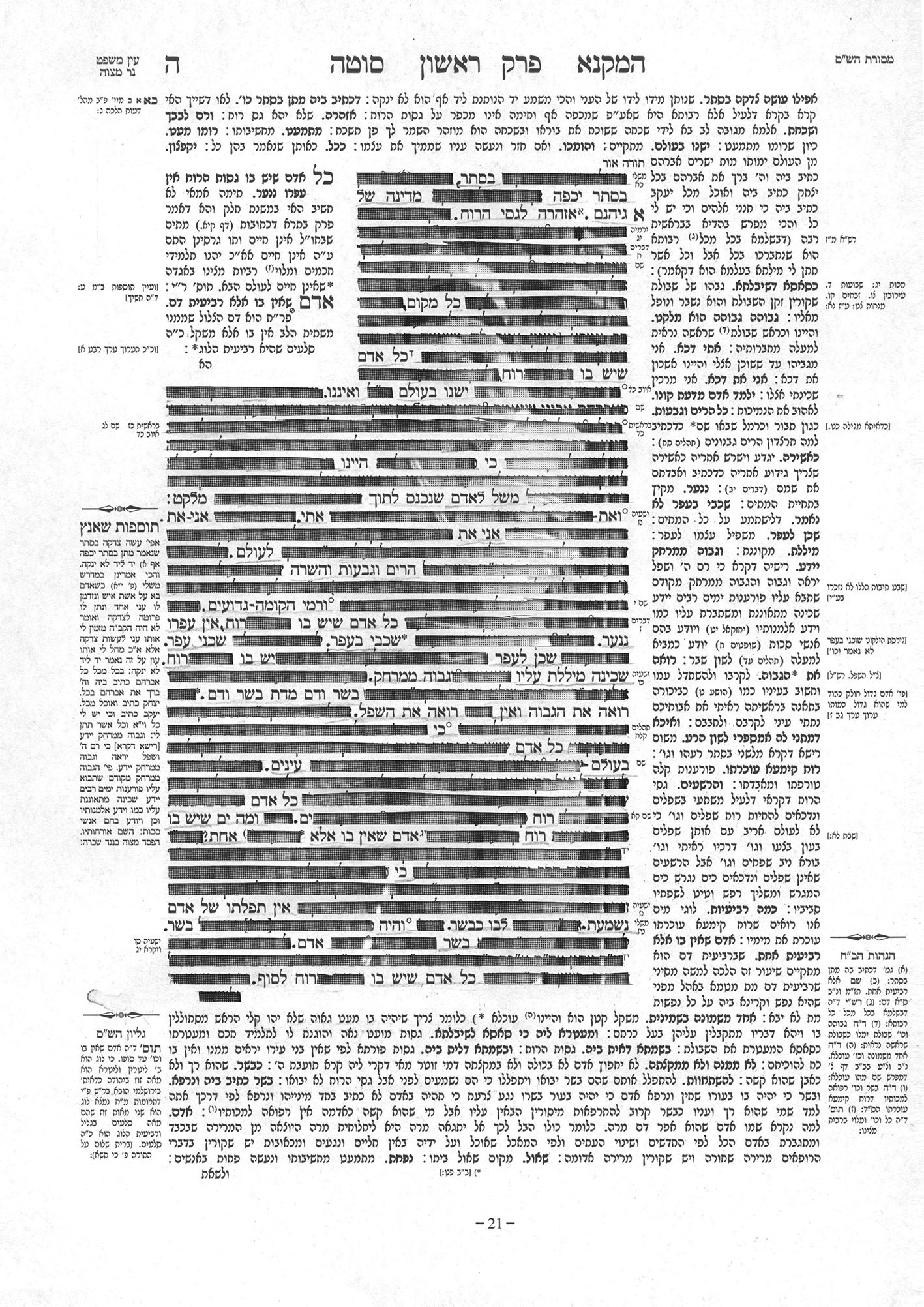

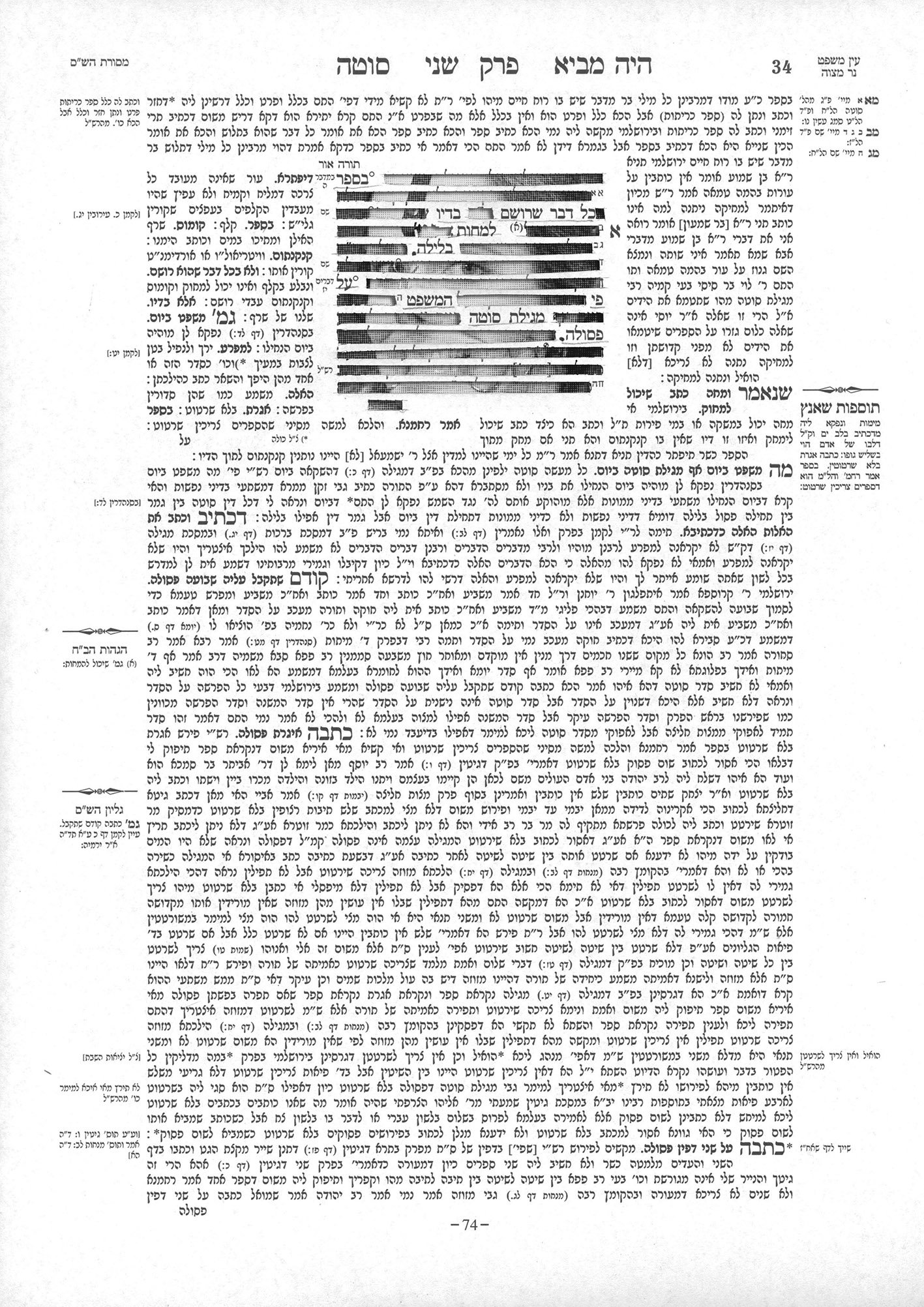

The Talmud serves as a formal guideline for the Rabbinic and Israeli legal systems, which are characterised by male supremacy and sexism. The installation takes on the responsibility of repositioning the narrative by displaying and deconstructing an original copy of tractate Sotah of the Women's Order, which describes one of the most brutal rituals in Rabbinic literature. Using a technique titled Erasure Poetry it effaces and reinterprets the standard version and reshapes the discourse. Primarily it layers diverse perspectives of thinkers and creators of different backgrounds, generations, and fields, such as Y. Wallach's poetry on the walls and R. Neis's reflective contribution, critically examining the construction and regulation of gender in the tradition as in current times.

The Talmud (תלמוד) is an elucidation of the Mishnah (משנה; study by repetition) that was redacted at the beginning of the 3rd century CE. It is the first major written collection of Jewish oral traditions and the first extensive work of Rabbinic literature. The Talmud is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of religious law and theology. It is the anchor of Jewish ethics and is the substructure of its inclination, serving also as the guide for daily life. It is the formal guideline of the contemporary Rabbinic law system. In the present structure of the State of Israel, state laws are dictated by its content, as its teachings are intertwined within almost every subject. The Rabbinate has autonomous authority on innumerable laws and rulings, mostly related to migration, marriage, divorce, birth and death - most significant of life events. These laws are systematically characterised by principle of male supremacy. Above all, change is not lurking in the horizon, as women are strictly forbidden to serve as judges or take over any position of power in the Rabbinate.

Women’s Order (סדר נשים) is the third arrangement in 6 sub-arrangements of the Mishnah. It tackles mainly family law; marriage and divorce, the obligations of spouses towards each other and their children, women’s infidelity, succession and wills. By the Talmud, the word suggesting Women’s Order is “חֹסֶן”, since its source also means ‘succession’ and the woman gives birth to successors. Overall, this arrangement discusses contracts that refer to capital and its transmission.

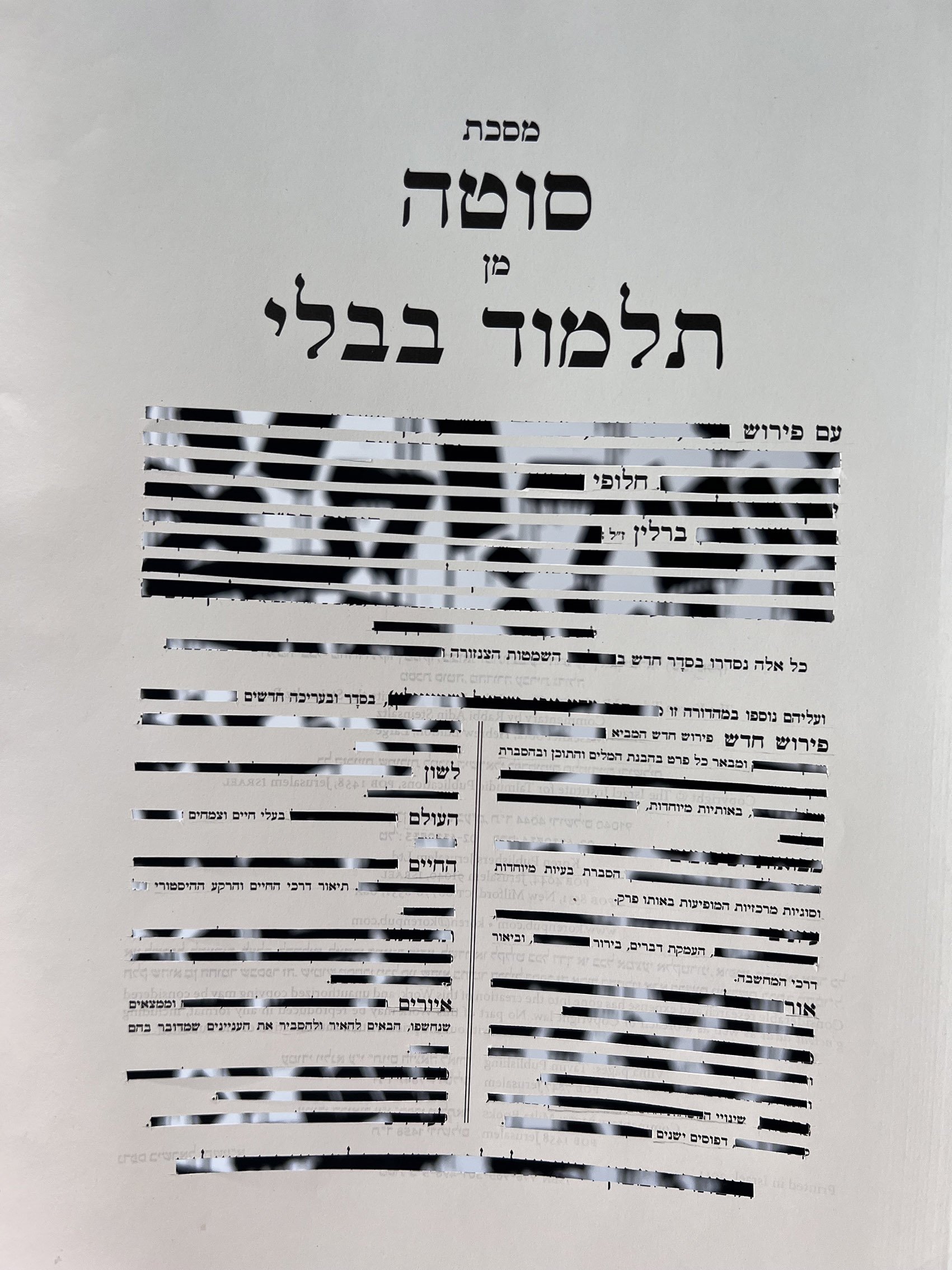

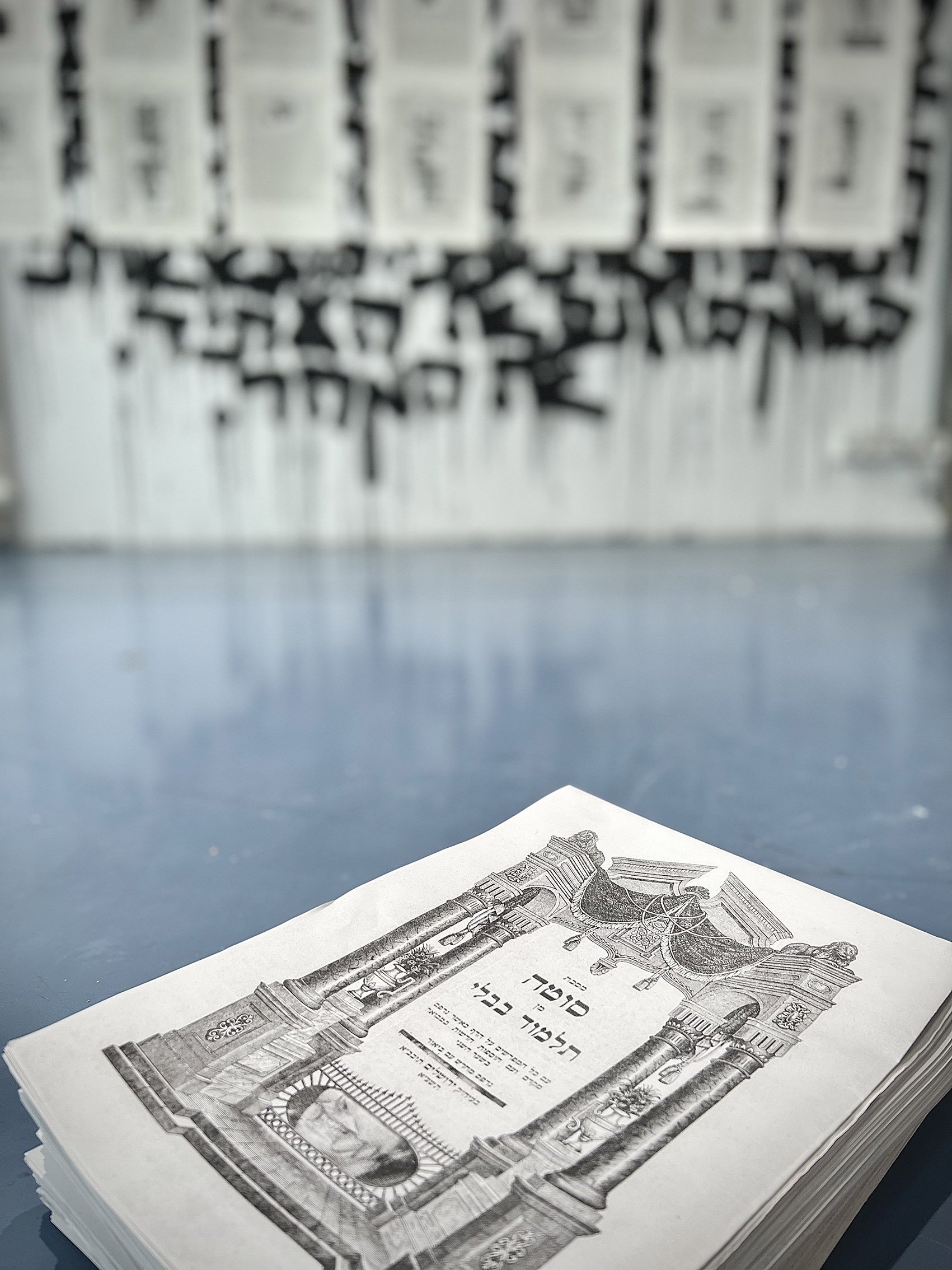

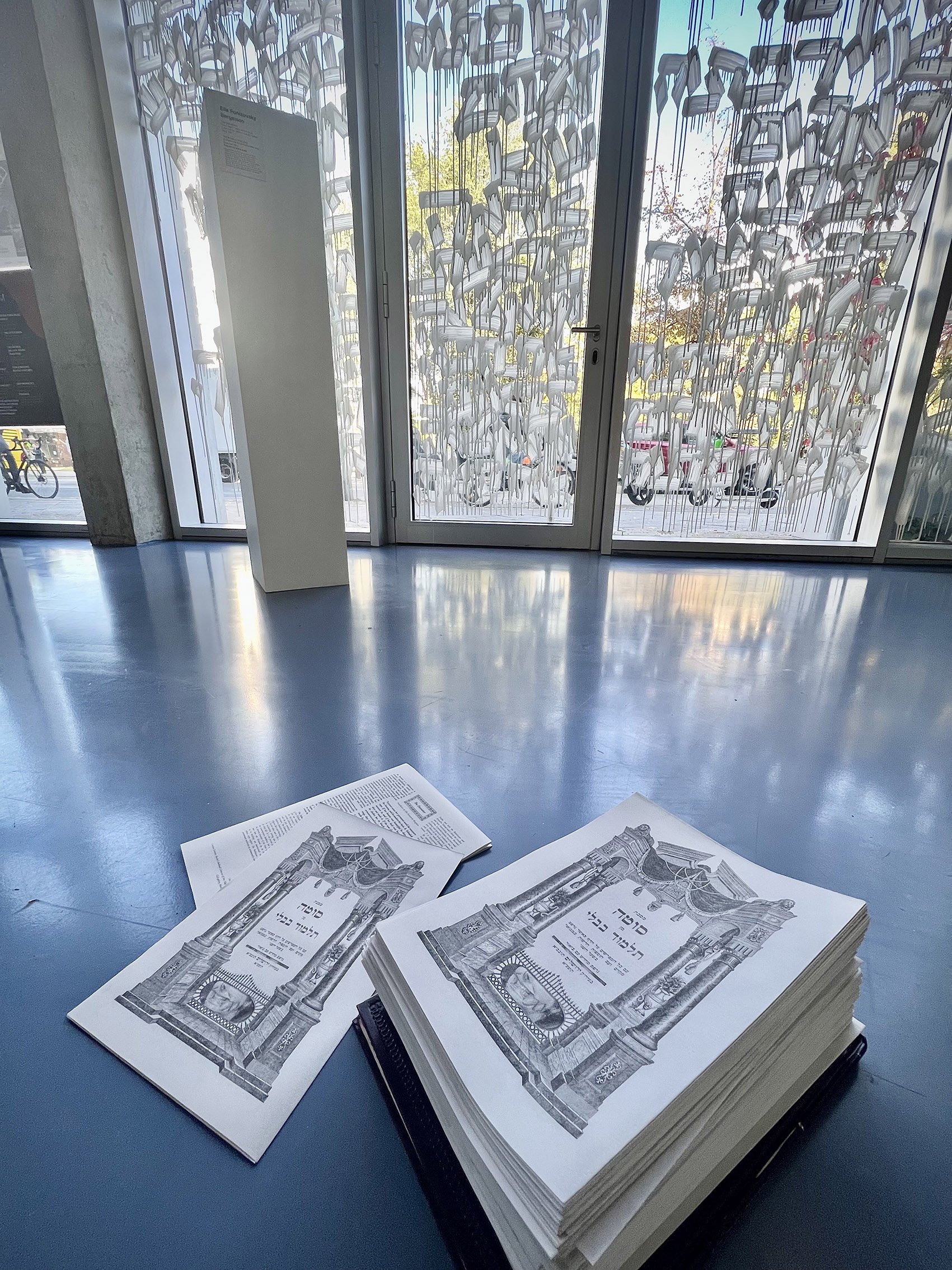

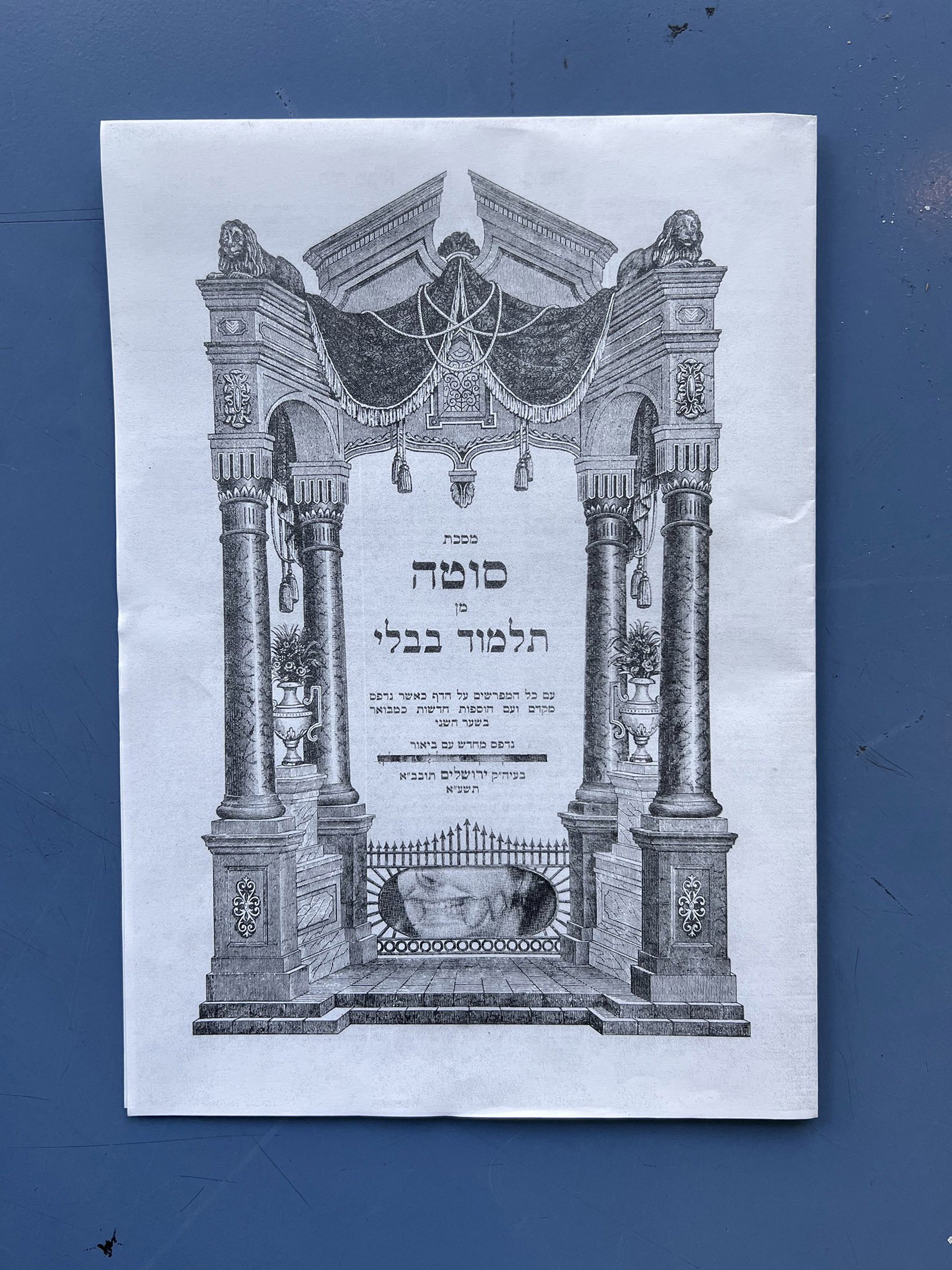

Masechet Sotah (מסכת סוטה; perverted, deviated, in female form) is the fifth tractate in Women’s Order, that explains the ordeal of the Bitter Waters, a trial of a woman suspected of adultery, which is prescribed by the Bible. The tractate exists in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and both the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud and is likely the cruellest and most humiliating procedure described in them. A parallel tractate, that treats male jealousy and possessive tendencies, does not exist. Above all this book permits, promotes and legitimises radical brutality against women. It is mass-printed and studied by approximately 15.2 million (and rising) people worldwide nowadays.

The Ritual: the Torah determines that a husband who suffers from “a spirit of jealousy” and suspects his wife must bring her to the priest, who performs a series of ritual acts: he offers a “meal-offering of jealousy,” an offering of ground barley, unbinds her clothes and hair, makes her swear an oath that she had sexual relations with no man other than her husband, writes the oath in a scroll and erases it in water mixed with dust from the Tabernacle, and finally forces the woman to drink the mixture. This mixture, “the bitter, curse-causing waters”, contains the oath and the curses that accompany it, and ultimately determines the woman’s fate. As the woman drinks the potion, the outcome of the trial appears on her body, confirming or refuting her husband’s suspicions: if she is guilty, the water will cause the woman to become infertile (the expressions “her thigh falls” and “her belly distends” are probably euphemisms for harm to the sexual organs). If she is innocent the water will do her no harm and even cause her to become fertile.

“A priest seizes her garments until he uncovers her bosom, and he undoes her hair. R. Yehudah says: If her bosom was beautiful he does not uncover it, and if her hair was beautiful he does not undo it. If she was clothed in white, he clothes her in black; if she wore golden ornaments and necklaces, ear-rings and finger-rings, they remove them from her in order to make her repulsive. After that the priest takes a rope and binds it over her breasts. Whoever wishes to look upon her comes to look.”

Masechet Sotah 1:5–6

Produced by Gravel Studio. Director & Editor Aviv Kosloff. DoP Takehiro Nozu.

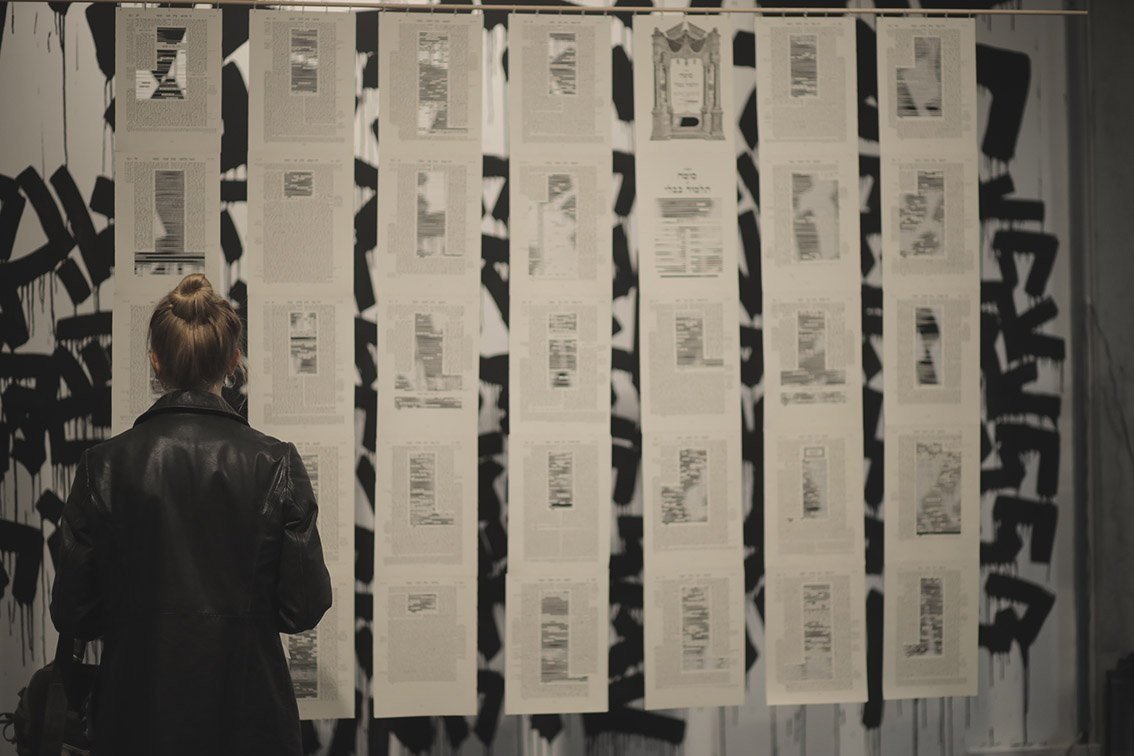

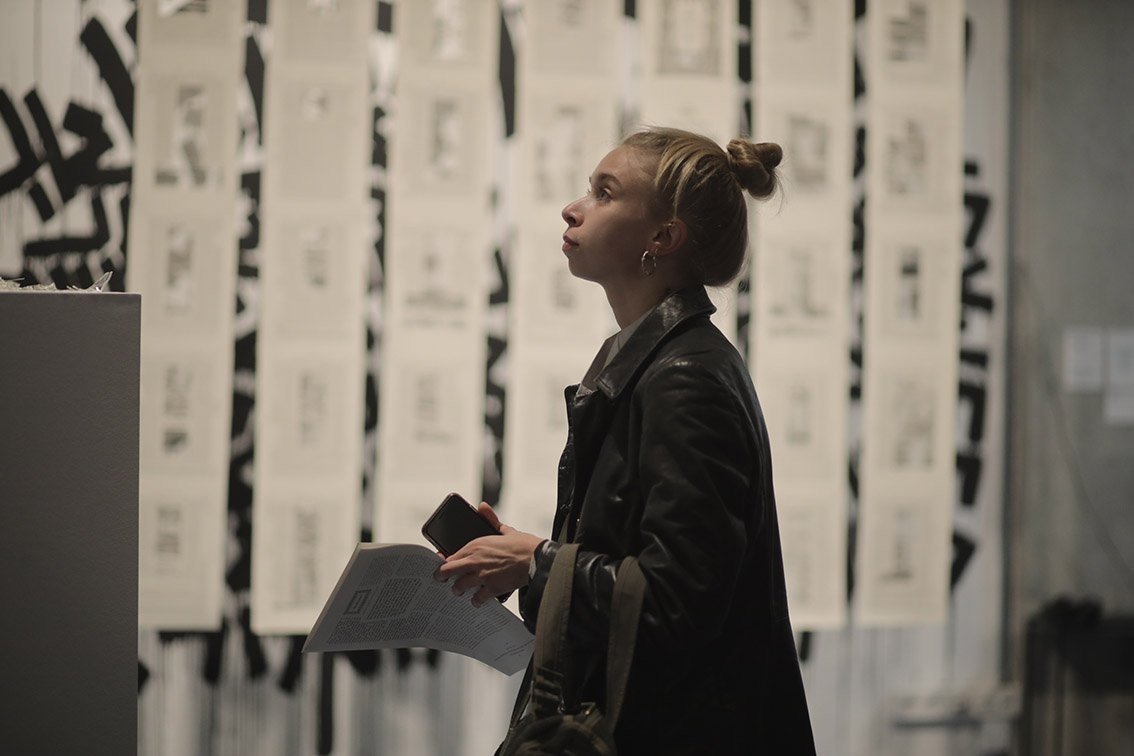

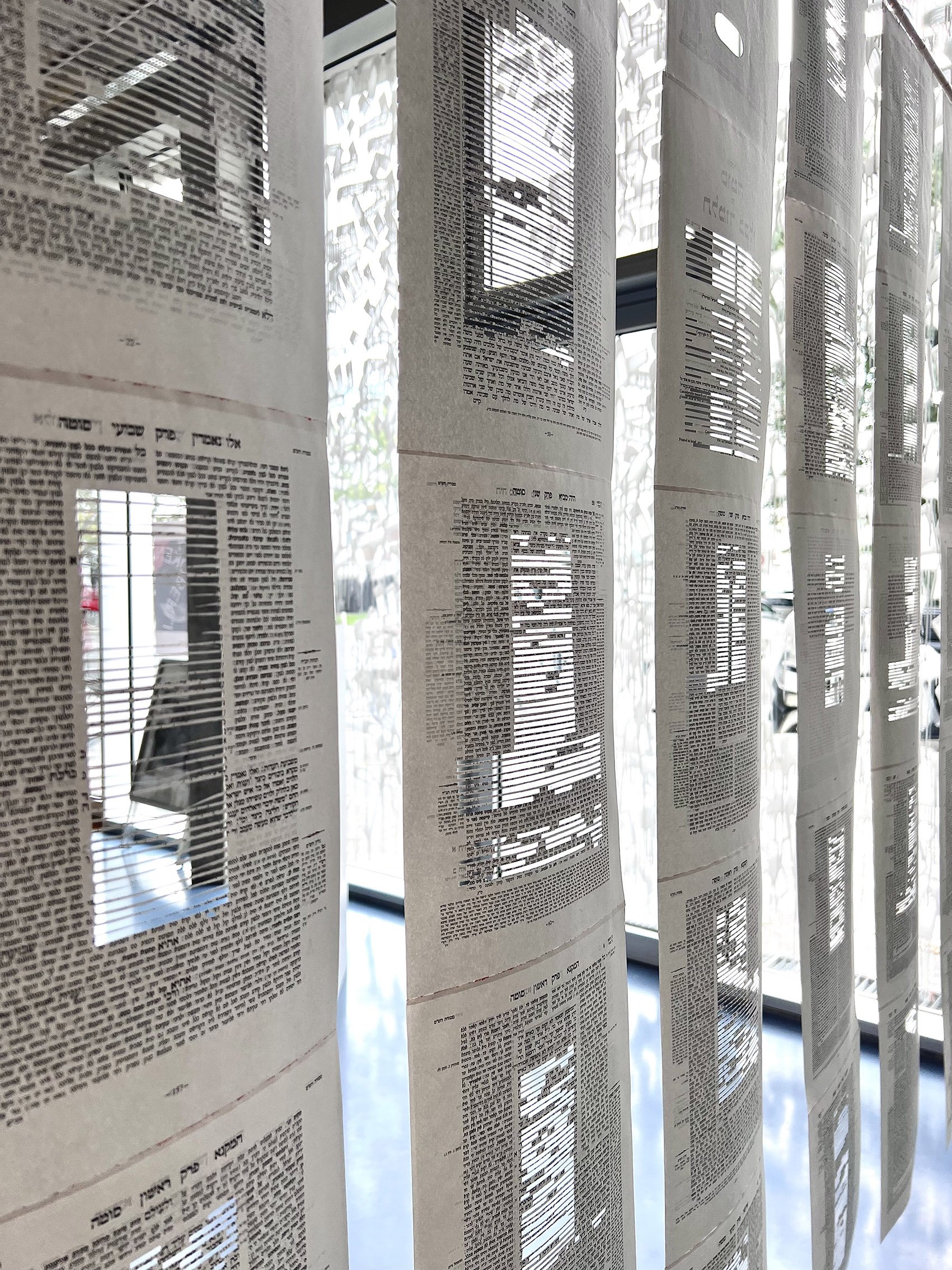

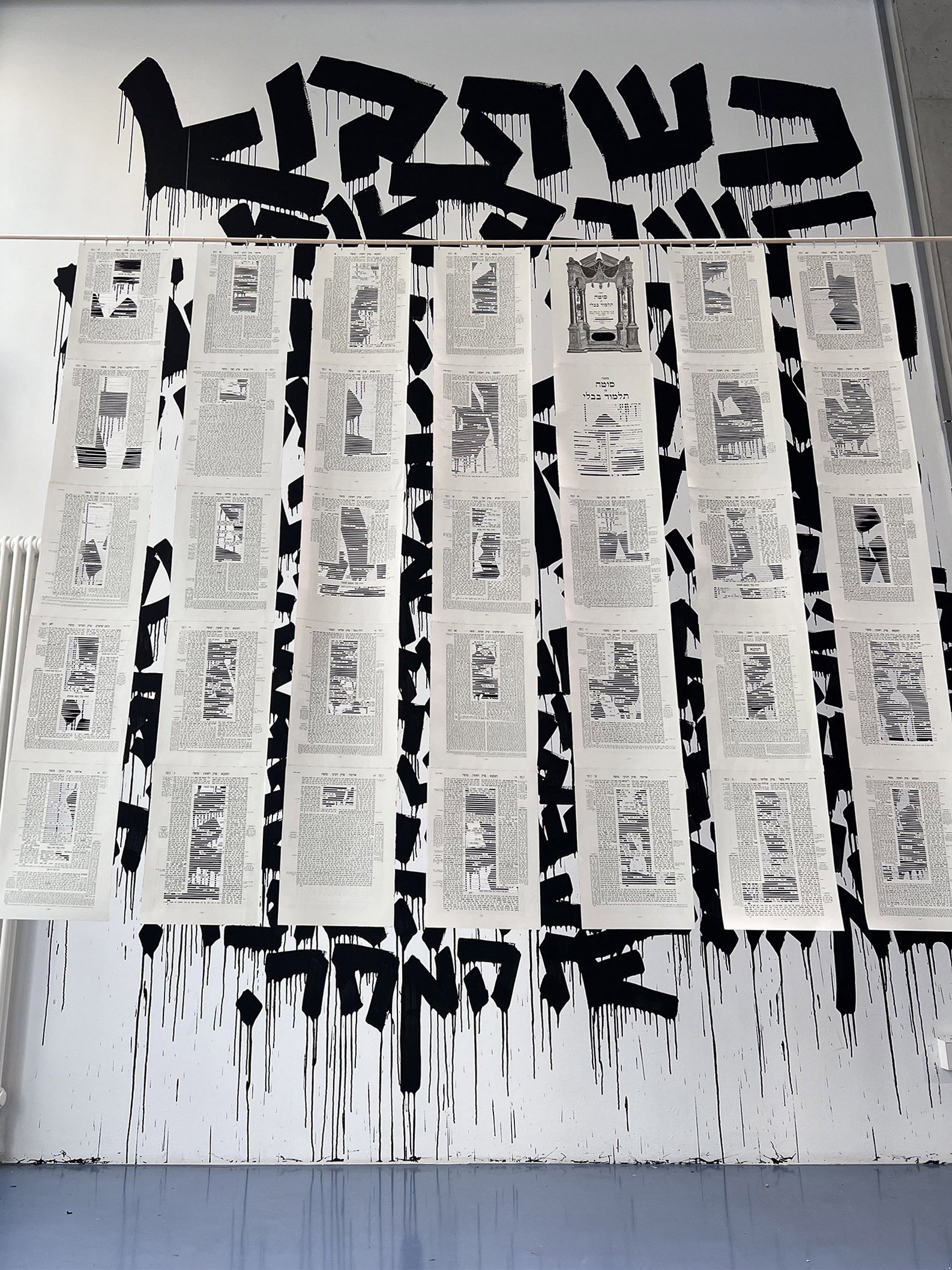

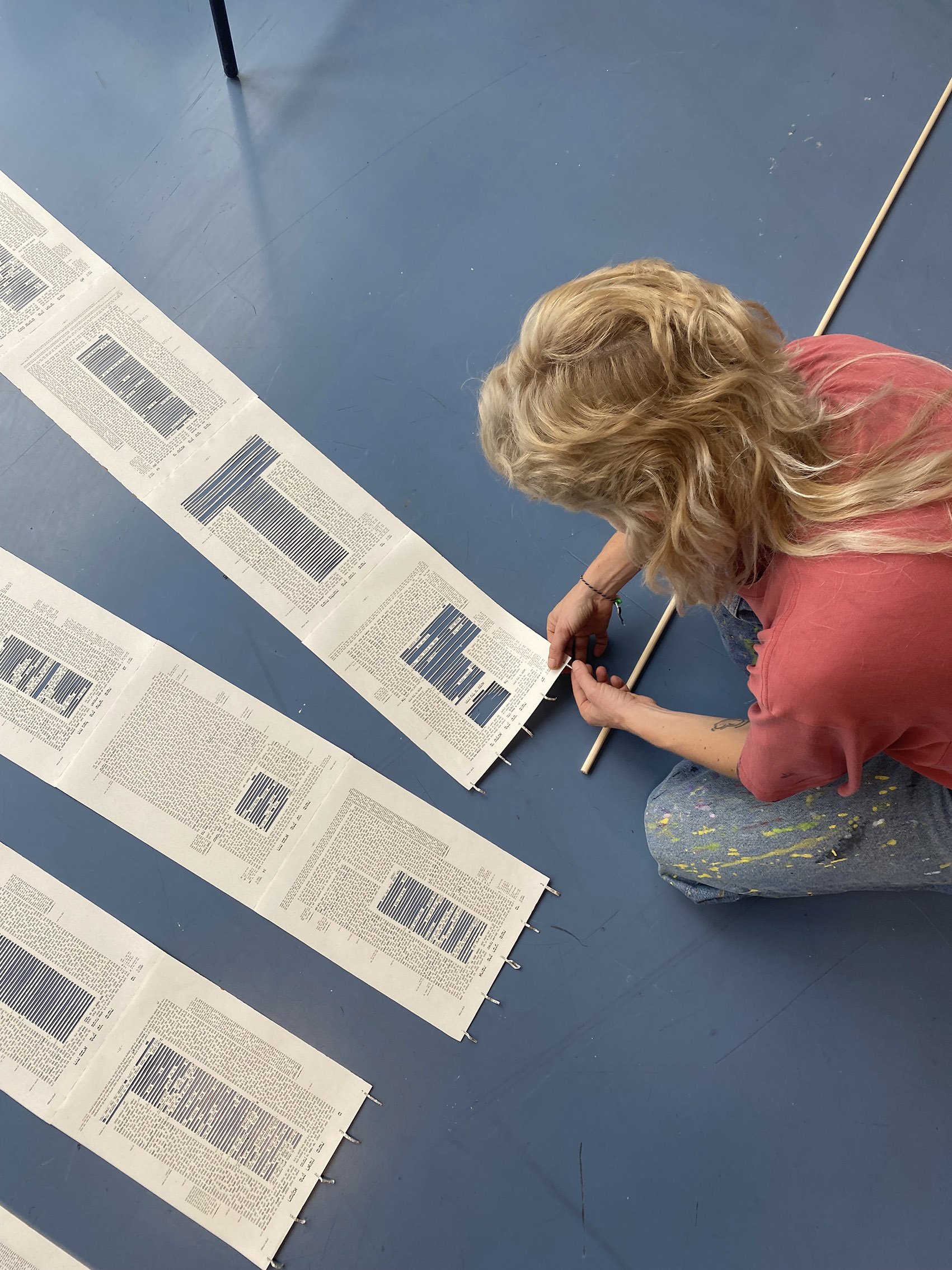

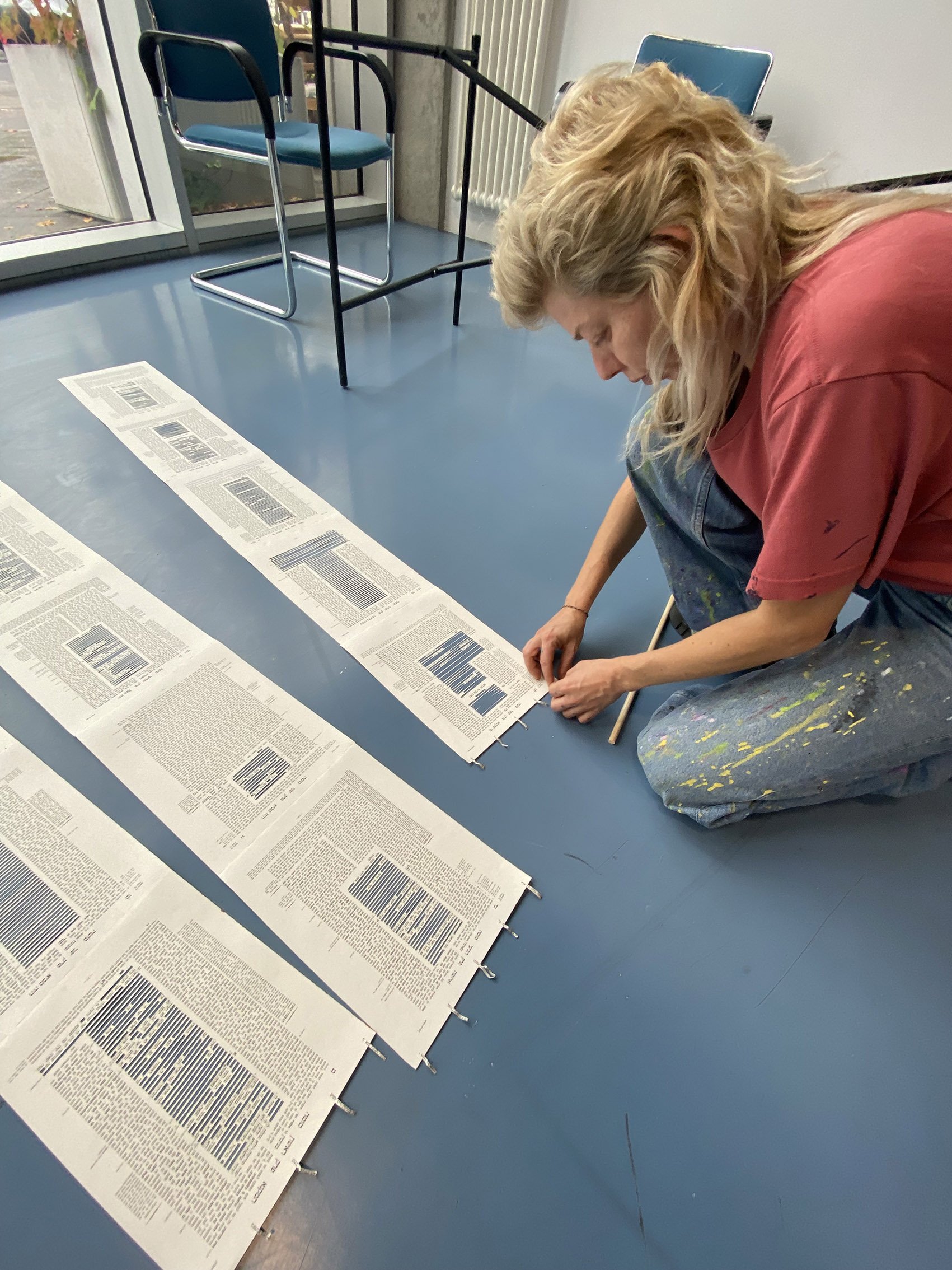

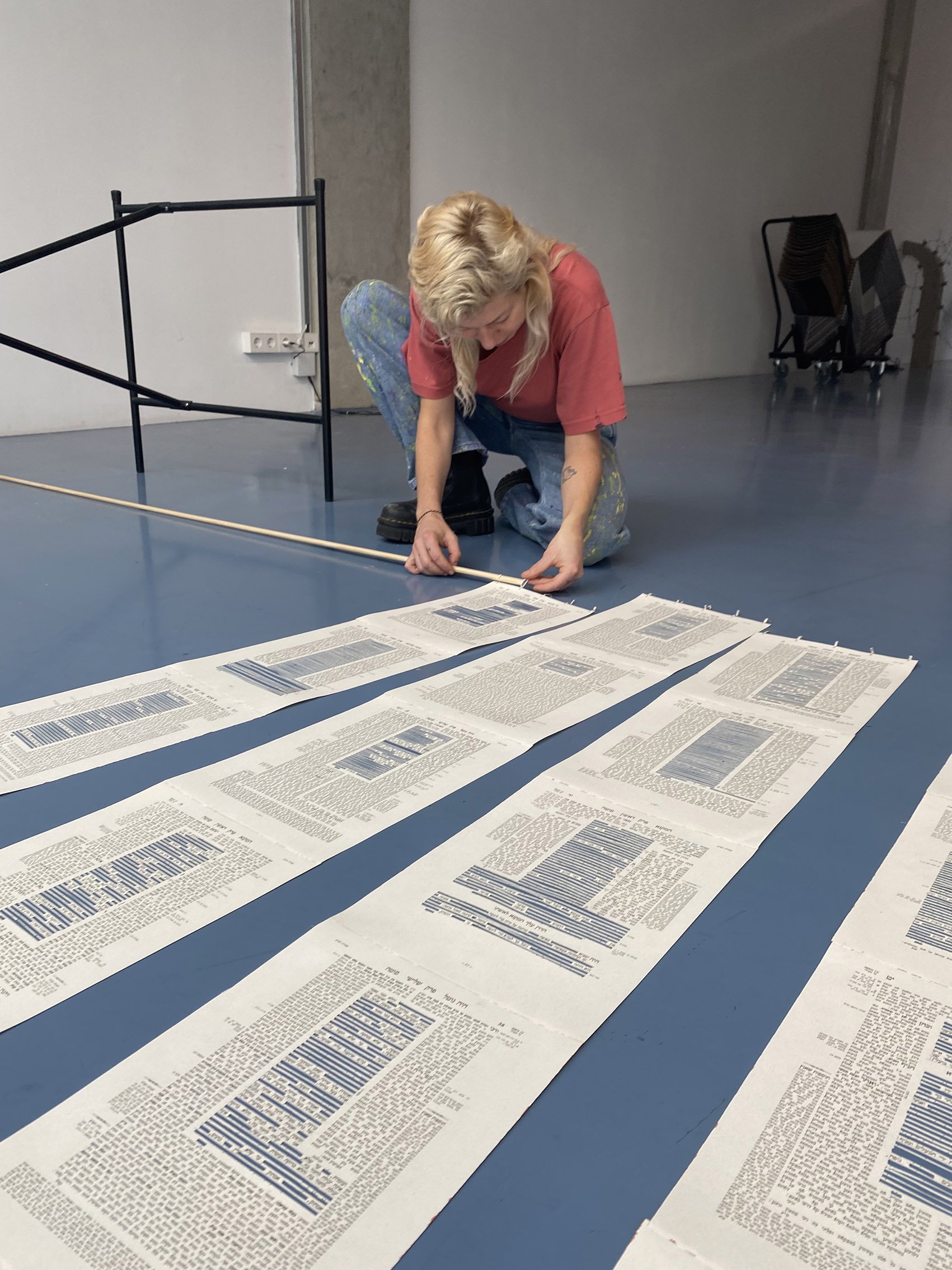

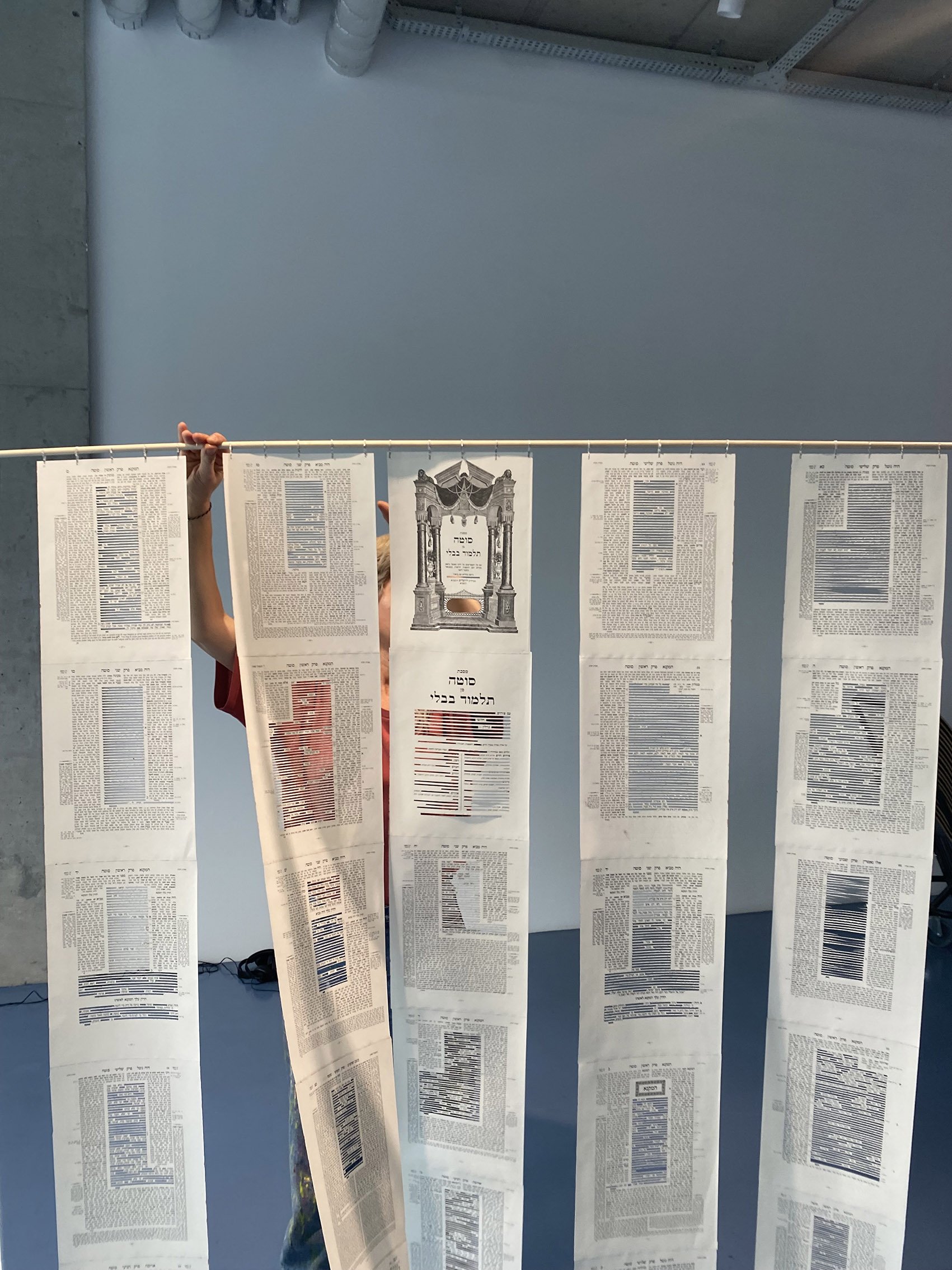

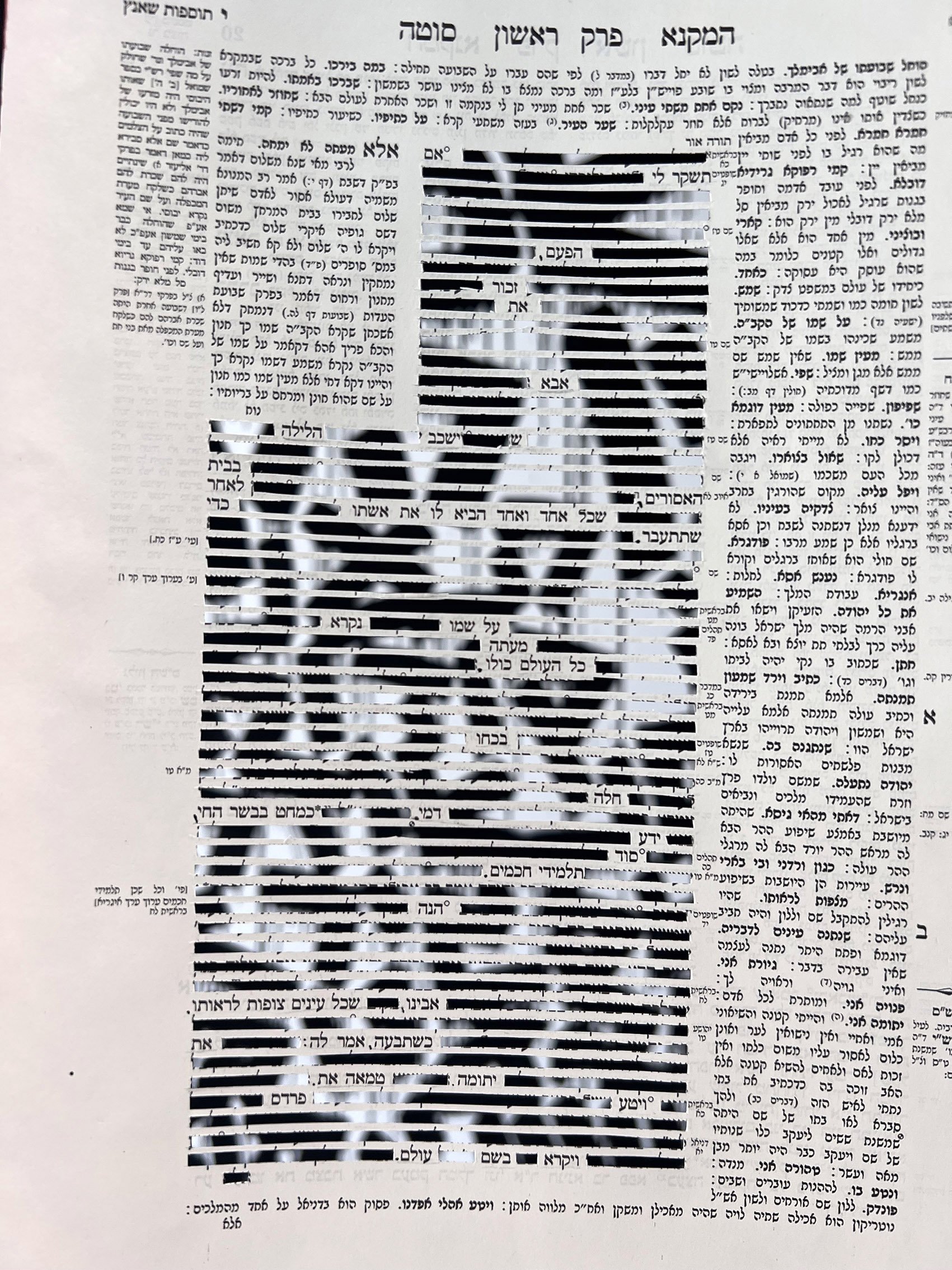

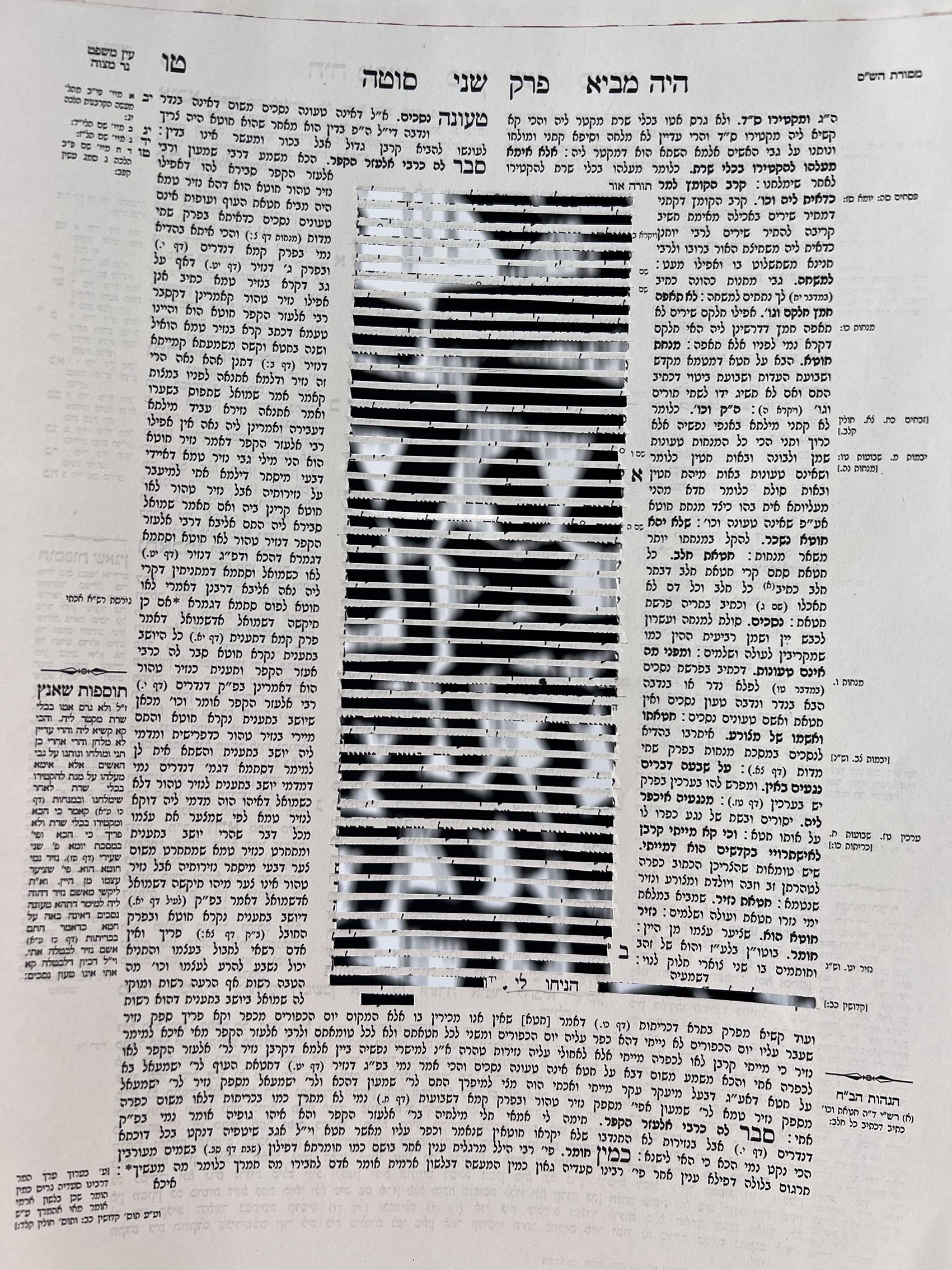

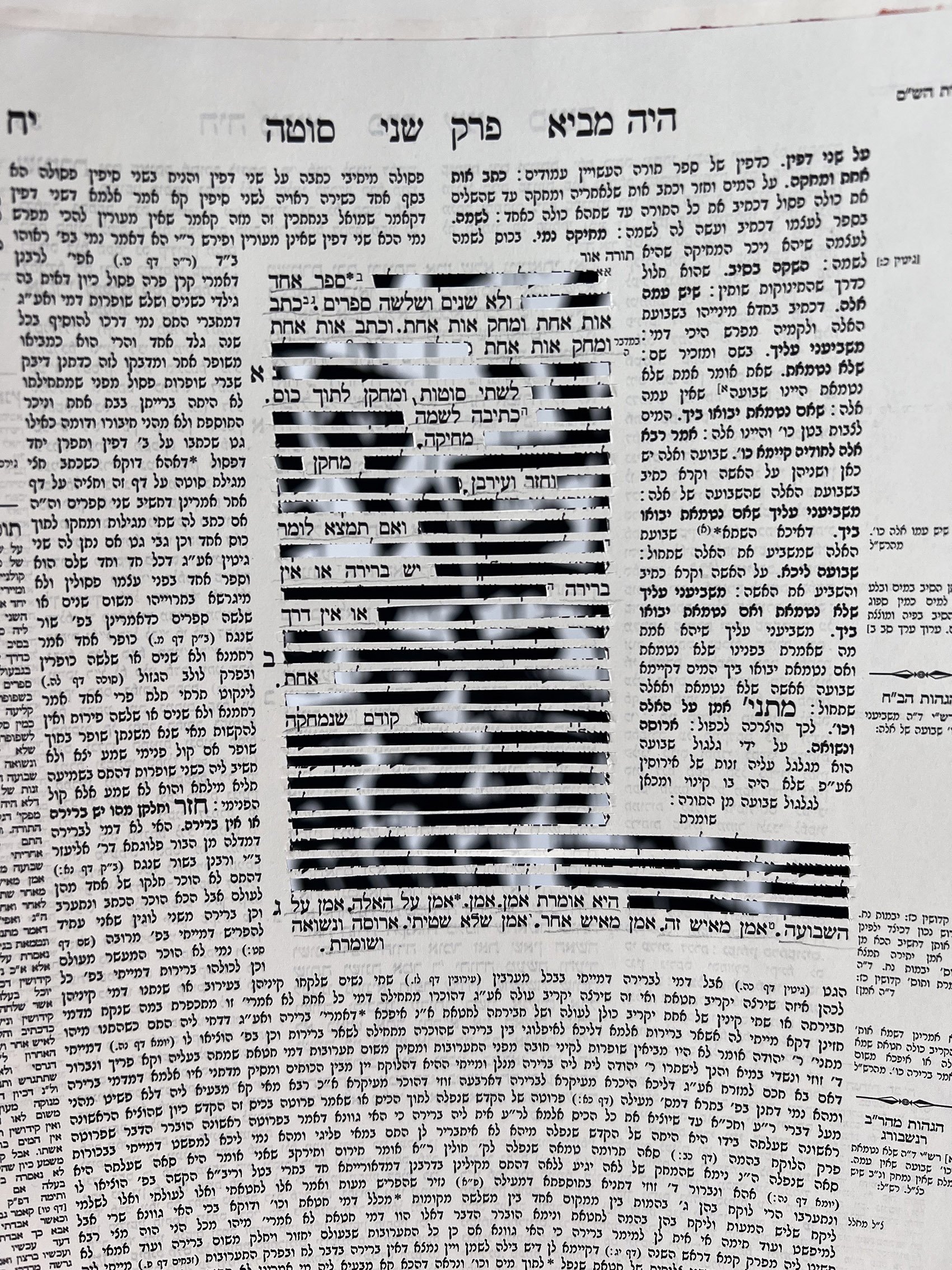

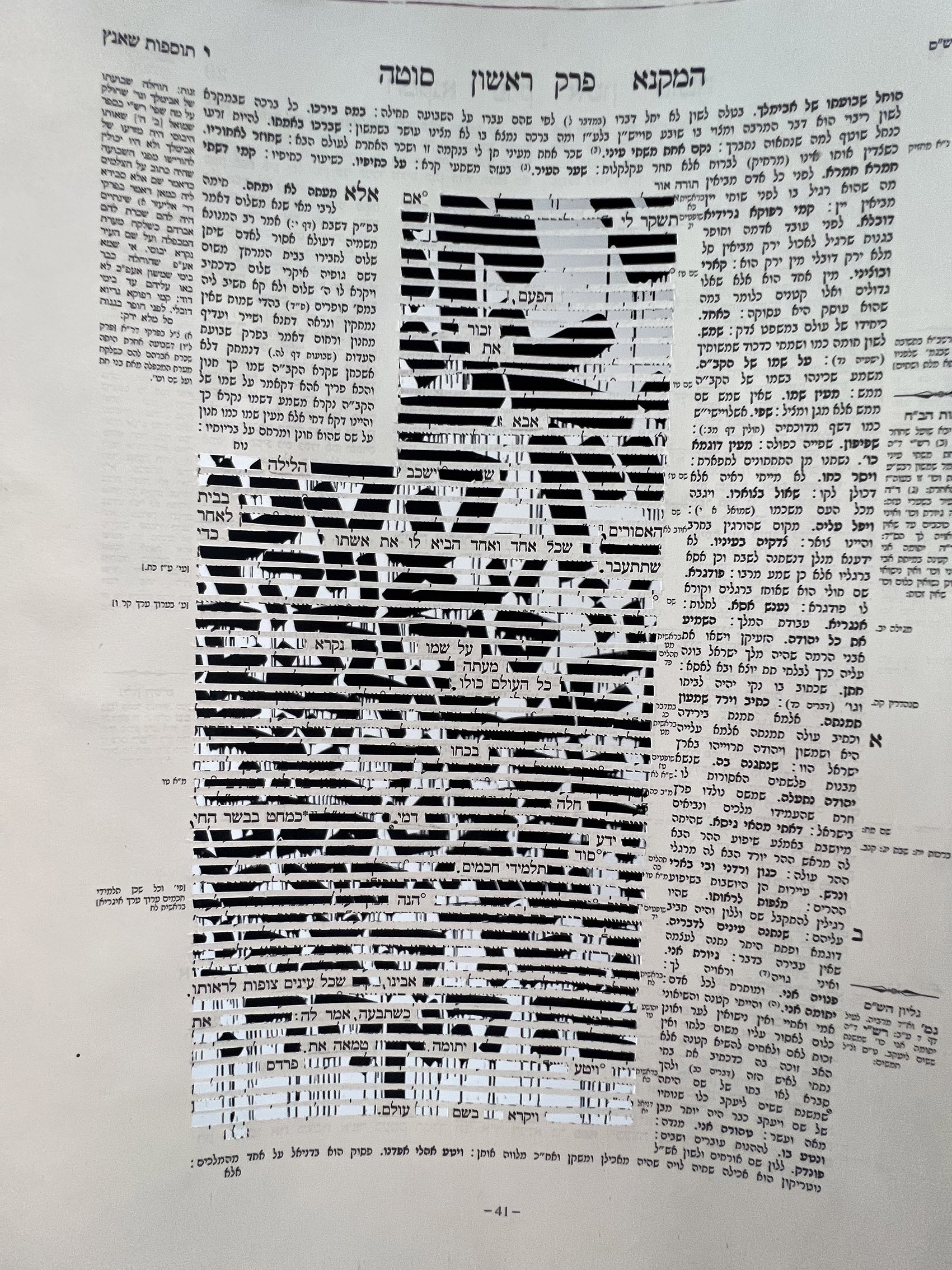

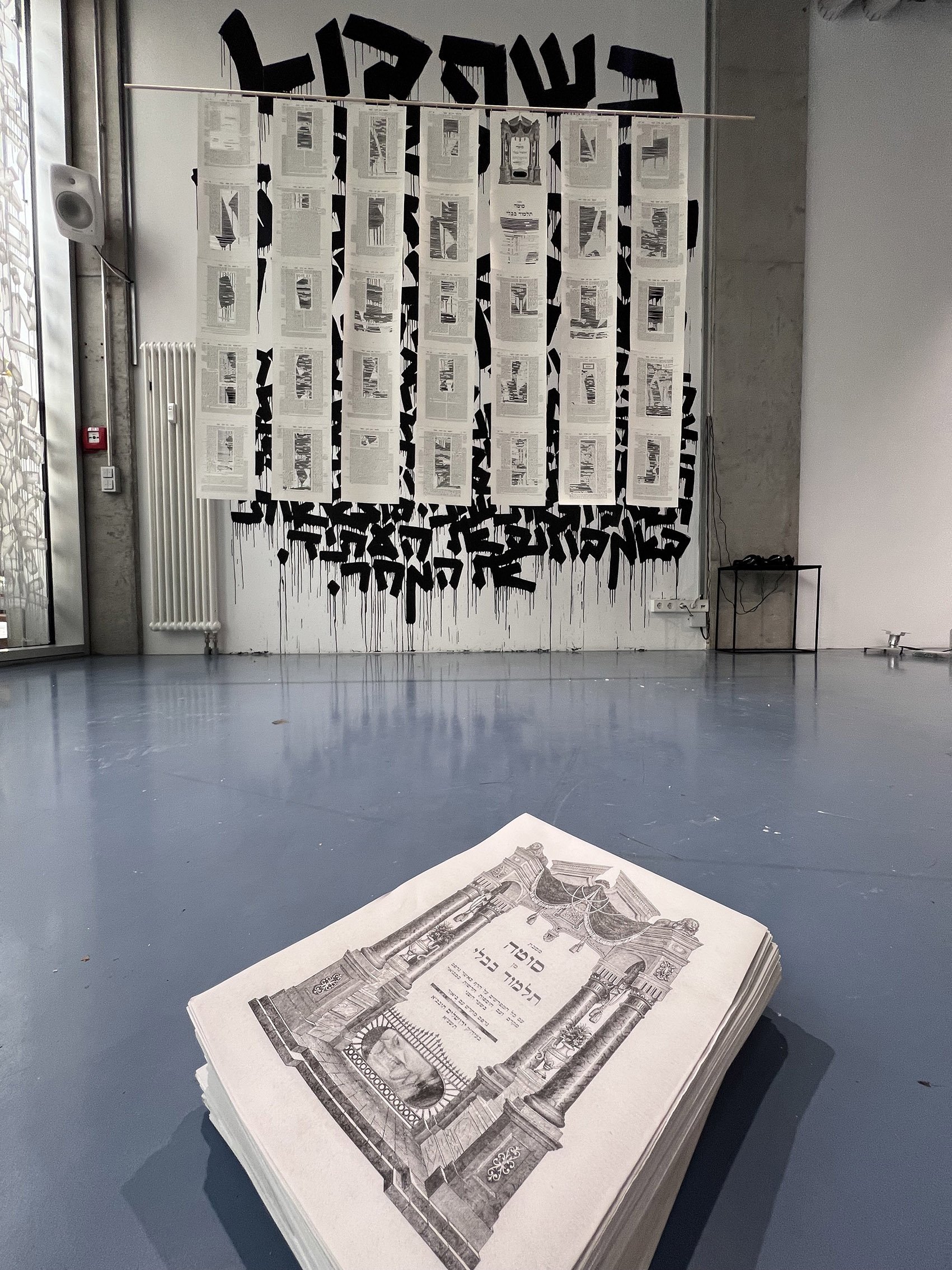

Part 1: The Deviator

Erasure poetry, based on Sotah tractate, Women’s Order, Talmud Bavli, 240 x 150 cm

Part of the Jewish tradition is systematic discrimination of women originating in interests of capital possession. In Israel, due to the lack of separation between religion and state laws, the discrimination is legally maintained to the present-day. The Deviator reaches out to the source, as it uses the Talmud as raw material. Its protest tactic is removing text, leaving a grid empty of its former content, also leaving individual words to form a new text. A new narrative is thus retrieved.

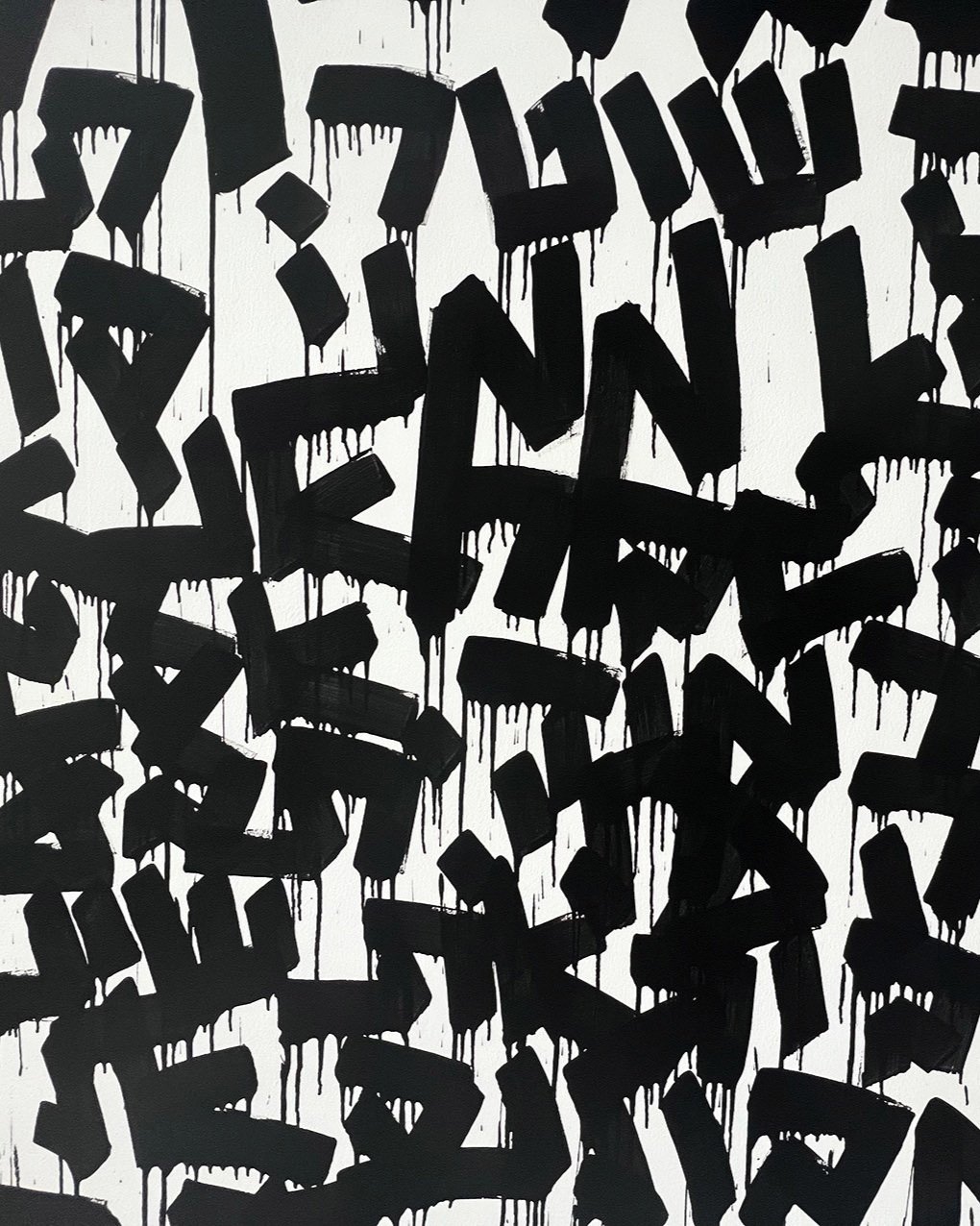

Part 2: When You Will Come

A temporary wall mural. Based on a poem by Yona Wallach. Acrylic Paint on Gallery Wall, 420 x 330 cm.

Yona Wallach (1944 – 1985) was an Israeli feminist and postmodernist poet. Both in her life and work she was submerged into exploring sexuality, Jewish tradition and mysticism. She is considered one of the greatest, most revolutionary and provocative Israeli poets. Her work penetrated the mainstream firstly by receiving condemnation directly from the Deputy Minister of Education and Culture, Miriam Tessa Glazer, who after the publishing the poem 'Tefillin' announced in an interview: “Wallach is simply disturbed. A horny beast who writes such a poem and even publishes it... it's a murky wave... anarchy". This event poses a major success in calling-out the Israeli government for its conservative worldview and provokes a broad public debate. The absurdity of this anecdote is, that Wallach’s poetry straingly echoes Sotah, which is referred to by scholars as “Rabbinic pornography” (Sarra Lev) and as “a fantasy of a total and unbridled control over the female body” (Ishay Rosen-Zvi). When compared, 'Tefillin' is not more of a pornographic literary creation then the Rabbinic literature itself. One has to ask themselves, to what extent the misogynistic sadism that Wollach's poetry reveals is in fact rooted in the Jewish tradition and leakes into the Jewish and Israeli unconscious perception?

Wallach experienced herself as a medium, a profit. Though she grew up in a secular home and had no religious education, and despite the radicality of her non-confirmative lifestyle and work, she believed in God. She confessed to Helit Yeshurun during the last interview shortly before her death: “I believe in him. The question is whether he believes in me." Yeshurun concludes: “No poet of Jonah's generation spoke about God. She managed to do the incomprehensible: separate faith and religion. [...] Faith and heresy. She declared that she is free from good and evil, but that was her ground assomption: good and evil. And to do evil is also a valu: to sin as only a believer can.” Yeshurun adds: “Duplicity. She was two all the time; a woman and a man, a believer and a hereser. Her perfection was only in being divided and torn.” Wallach died as she was 41 years old, defeated by breast cancer that she refused to treat. Her fearless stare directly into the eyes of death was supposedly one of her poetic experiments. She never married or had children.

כשתבוא

כשתבוא לשכב איתי

תלבש מדים של שוטר

אני אהיה העבריין הקטן

אתה שוטר

תענה אותי

תוציא ממני סודות

אני לא אהיה גבר

אני אודה

אשבר

אזמר מיד

אסגיר את כולם

תירק עלי

תבעט בבטני

תשבור את שיני

הוצא אותי באמבולנס

אל העתיד

אל המחר.

When You Will Come

When you will come to sleep with me

Wear police uniform

I'll be the little criminal

You are a cop

Torture me

Take secrets out of me

I will not be the man

I will confess

I will break

I will squeal instantly

I will turn everyone in

Spit on me

Kick my stomach

Break my teeth

Take me out in an ambulance

To the future

To the tomorrow.

Part 3: When You Will Come To Sleep With Me Like God

A temporary window mural. Based on a poem by Yona Wallach (1944 – 1985). Lime paint on glass, 420 x 460 cm.

כשתבוא לשכב אתי כמו אלוהים

תָּבוֹא לִשְׁכַּב אִתִּי כְּמוֹ אֱלֹהִים

רַק בָּרוּחַ

עַנֵּה אוֹתִי כְּכֹל שֶׁתּוּכַל

הֱיֵה לֹא מֻשָּׂג לְעוֹלָם

הַנַּח לִי בְּסִבְלִי

אֶהְיֶה בְּמַיִם עֲמֻקִּים

לְעוֹלָם לֹא אַגִּיעַ לַחוֹף.

גַּם לֹא בְּמַבָּט

לֹא בְּהַרְגָּשָׁה

אוֹ בְּמַבּוּל

מַיִם לְמַטָּה וּמִלְּמַעְלָה

לְעוֹלָם לֹא שָׁמַיִם

אֲוִיר פָּתוּחַ

הַמָּקוֹם הַפָּתוּחַ הֲכִי סָגוּר בָּעוֹלָם

מָקוֹם פָּתוּחַ

תָּמִיד מָקוֹם סָגוּר פָּתוּחַ

לֹא פָּתוּחַ וְלֹא סָגוּר

כְּלוֹמַר סָגוּר פָּתוּחַ

כְּלוֹמַר לֹא סָגוּר וְלֹא פָּתוּחַ

לְעוֹלָם שֶׁלֹּא אֲדַמֶּה

לִרְאוֹת מִלְּמַעְלָה אֶת הַכֹּל

לִרְאוֹת מִלְּמַעְלָה אֶת הַנּוֹף

הֱיֵה רַק רוּחָנִי

כְּאֵב נָקִי וּמְבֻדָּד כִּצְלִיל כְּאֵב

לְעוֹלָם שֶׁלֹּא אֶגַּע

לְעוֹלָם שֶׁלֹּא אֵדַע

לְעוֹלָם שֶׁלֹּא אַרְגִּישׁ מַמָּשׁ

אַף פַּעַם לֹא מַמָּשׁ

כְּמוֹ כֹּל הָאֵלֶּה שֶׁלְּךָ

תָּמִיד בַּדֶּרֶךְ.

When You Will Come To Sleep With Me Like God

Come sleep with me like God

Only in spirit

Torture me as much as you can

Be unreachable forever

Leave me in my suffering

I will be in deep waters

I will never reach the beach.

Not even with a glimpse

Not in the feeling

or in a flood

Water below and from above

Never sky

Open air

The most closed open place in the world

Open place

Always a closed open place

Neither open nor closed

Namely closed open

Namely neither closed nor open

Never a land

To see everything from above

To see the view from above

Be only spiritual

Pure and isolated pain as the sound of pain

So I will never touch

So I will never know

So I will never really feel

Never really

Like all those of yours

Always on the way.

Part 4: Labour

A sound piece. 9’0 minutes, looped.

How do one express through the medium of sound the lack of a voice? In Sotah in particular and in the Talmud in general, women are objectified to become birth-giving organisms. A reflection on that is the sound of the breath of a birth giver.

Recording by Kaity Fox, a birth doula and a multidisciplinary artist. Her practice as a birth worker is focused in holistic birth education, continuity of care for families before, during and after birth and questioning and bringing to light the current systemic issues around birthing in Germany.

Part 5: The Bitter Waters

Found objects, arranged; coal, glass, verses out of Sotah tractate.

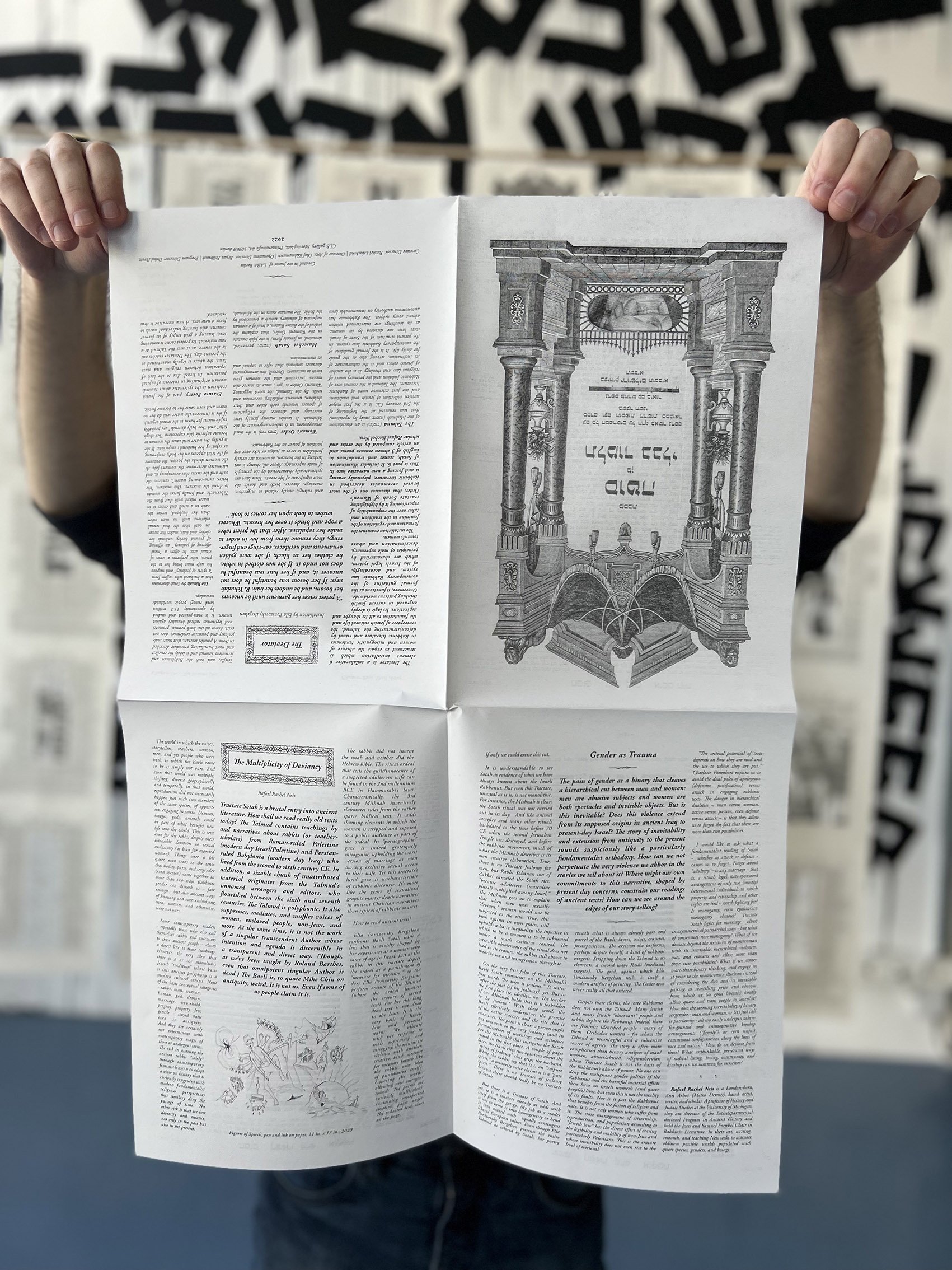

Part 6: The Multiplicity of Deviancy

A reflection by Rafael Rachel Neis. A handout, riso-print on paper, 50 x 70 cm.

Rafael Rachel Neis is a London-born, Ann Arbor (Metro Detroit) based artist, writer, and scholar. A professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, they are director of the Interdepartmental doctoral Program in Ancient History and hold the Jean and Samuel Frankel Chair in Rabbinic Literature. In their art, writing, research, and teaching Neis seeks to activate old/new possible worlds populated with queer species, genders, and beings.

The Multiplicity of Deviancy

Rafael Rachel Neis

Rafael Rachel Neis, Figures of Speech, pen and ink on paper, 11 in. x 17 in., 2020

Tractate Sotah is a brutal entry into ancient literature. How shall we read really old texts today?

The Talmud contains teachings by and narratives about rabbis (or teacher-scholars) from Roman-ruled Palestine (modern day Israel/Palestine) and Persian-ruled Babylonia (modern day Iraq) who lived from the second to sixth century CE. In addition, a sizable chunk of unattributed material originates from the Talmud’s unnamed arrangers and editors, who flourished between the sixth and seventh centuries. The Talmud is polyphonic. It also suppresses, mediates, and muffles voices of women, enslaved people, non-Jews, and more. At the same time, it is not the work of a singular transcendent Author whose intention and agenda is discernible in a transparent and direct way. (Though, as we’ve been taught by Roland Barthes, even that omnipotent singular Author is dead.) The Bavli is, to quote Mike Chin on antiquity, weird. It is not us. Even if some of us people claim it is.

The world in which the voices, storytellers, teachers, women, men, and yes people who were both, in which the Bavli came to be is simply not ours. And even that world was multiple, shifting, diverse geographically and temporally. In that world, reproduction did not necessarily happen just with two members of the same species, of opposite sex, engaging in coitus. Demons, images, gods, animals could be part of what brought new life into the world. This is true even for the rabbis despite their ostensible devotion to sexual exclusivity (at least for married women). Things were a bit queer, even trans in the sense that bodies, parts, and sexgender (even species!) came together in more than two ways. Rabbinic gender can disturb us - fair enough - but also ancient ways of knowing and even embodying men, women, and otherwise, were not ours.

Some contemporary readers - especially those who also call themselves rabbis and successors to these ancient people - claim a direct line to these teachings. However, the very idea that there is a or the monolithic Jewish “tradition” whose basis is this ancient polyphony is a modern cultural conceit. None of the basic conceptual categories - rabbi, man, woman, human, god, demon, marriage, household, progeny, property, Jew, gentile - stayed static even in antiquity. And they are certainly not coterminous with contemporary usages of those or analogous terms. The risk in assessing the ancient rabbis *solely* through contemporary feminist lenses is to adopt a view on history that is curiously congruent with modern fundamentalist religious perspectives that similary deny the passage of time. The other risk is that we lose diversity and nuance, not only in the past but also in the present.

The rabbis did not invent the sotah and neither did the Hebrew bible. The ritual ordeal that tests the guilt/innocence of a suspected adulterous wife can be found in the 2nd millennium BCE in Hammurabi’s laws. Characteristically, the 3rd century Mishnah inventively elaborates rules from the rather sparse biblical text. It adds shaming elements in which the woman is stripped and exposed to a public audience as part of the ordeal. Its “pornographic” gaze is indeed grotesquely misogynist, upholding the worst version of marriage as men owning exclusive sexual access to their wife. Yet this tractate’s lurid gaze is uncharacteristic of rabbinic discourse. It’s more like the genre of sexualized graphic martyr death narratives in ancient Christian narratives than typical of rabbinic sources.

How to read ancient texts? Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson confronts Bavli Sotah with a lens that is vividly shaped by her experiences as a woman who came of age in Israel. Just as the rabbis in this tractate depict the ordeal as a punishment of “measure for measure,” so too does Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson perform erasure of the Talmud (where the ordeal involves the erasure of sacred text). For her this long dead text is not dead in the least. It is the very basis of Israeli law and personal status. We vibrate with her response to male supremacy and misogyny, she returns its violence with another, creative, kind: measure for measure (much like the rabbis’ own idea of punishment itself). Covering the words, allowing new emergent sounds. The poems are curiously multivalent, containing unexpected emotion, pain, anger. The redacted text, scars on the page.

Gender as trauma.

The pain of gender as a binary that cleaves a hierarchical cut between man and woman: men are abusive subjects and women are both spectacles and invisible objects. But is this inevitable? Does this violence extend from its supposed origins in ancient Iraq to present-day Israel? The story of inevitability and extension from antiquity to the present sounds suspiciously like a particularly fundamentalist orthodoxy. How can we not perpetuate the very violence we abhor in the stories we tell about it? Where might our own commitments to this narrative, shaped by present day concerns, constrain our readings of ancient texts? How can we see around the edges of our story-telling?

If only we could excise this cut.

It is understandable to see Sotah as evidence of what we have always known about the Israeli Rabbanut. But even this Tractate, unusual as it is, is not monolithic. For instance, the Mishnah is clear: the Sotah ritual was not carried out in its day. And like animal sacrifice and many other rituals backdated to the time before 70 CE when the second Jerusalem Temple was destroyed, and before the rabbinic movement, much of what the Mishnah describes is its own creative elaboration. True, there is no Tractate Jealousy for men, but Rabbi Yohanan son of Zakkai canceled the Sotah rite: “because adulterers (masculine plural) multiplied among Israel.” The Mishnah goes on to explain that when men were sexually “deviant,” women would not be subjected to the rite. True, this push against its own grain, still upholds a basic inequality, the injustice in which to be a woman is to be subsumed under a man’s exclusive control. The ostensible obsolescence of the ritual does not lead to its erasure: the rabbis still choose to theorize sex and transgression through it.

On the very first folio of this Tractate, Bavli Sotah comments on the Mishnah’s first words “he who is jealous.” It states: “after the fact [of his jealousy], yes. But in the first place (ie, ideally), no. The teacher of our Mishnah holds that it is forbidden to be jealous.” With these words the Bavli effectively undermines the premise of the entire tractate and the rite that it examines. The point is clear: a person ought not succumb to the very jealousy (and its formalization of warnings and witnesses per the Mishnah) that instigates the Sotah ritual in the first place. A couple of pages later, the Bavli cites two opinions about the “spirit of jealousy” that grips the husband. While the rabbis say that it is an “impure spirit,” a minority voice claims it is a “pure spirit.” There is no Tractate of Jealousy because there should really be no Tractate of Sotah.

But there is a Tractate of Sotah. And yet, it is a tractate already at odds with itself from the get-go. My job as a reader is not to tame it into homogeneity or bend it into accord with equally contingent liberal European values. Even though Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson presents the entire Talmud as colored by Sotah, her poetry reveals what is always already part and parcel of the Bavli: layers, voices, erasures, juxtapositions. The excision she performs, perhaps despite herself, a kind of rabbinic exegesis. Stripping down the Talmud to its elements: a second wave Rashi (medieval exegete). The grid, against which Ella Ponizovsky Bergelson rails, is itself a modern artifact of printing. The Order was never really all that ordered.

Despite their claims, the state Rabbanut does not own the Talmud. Many Jewish and many Jewish “observant” people and rabbis deplore the Rabbanut. Indeed, there are feminist identified people - many of them Orthodox women - for whom the Talmud is meaningful and a subversive source of agency. The story is often more complicated than binary analyses of man/woman, abuser/abused, religious/secular, allow. Tractate Sotah is not the basis of the Rabbanut’s abuse of power. No one can deny the malignant gender politics of the Rabbanut and the harmful material effects these have on Israeli women’s (and queer people’s) lives, but even this is not the totality of its faults. Nor is it just the Rabbanut that benefits from the fusion of religion and state. It is not only women who suffer from it. The state management of citizenship, reproduction, and population according to “Jewish law” has the direct effect of erasing the legibility and viability of non-Jews and particularly Palestians. This is the erasure whose invisibility does not even rise to the level of retrieval.

“The critical potential of texts depends on how they are read and the use to which they are put.” Charlotte Fonrobert enjoins us to avoid the dual poles of apologetics (defensive justification) versus attack in engaging rabbinic texts. The danger in hierarchical dualities – man versus woman, active versus passive, even defense versus attack – is that they allow us to forget the fact that there are more than two possibilities.

I would like to ask what a fundamentalist reading of Sotah - whether as attack or defense - causes us to forget. Forget about “adultery!”: is any marriage - that is, a ritual, legal state-sponsored arrangement of only two (mostly) heterosexual individuals to which property and citizenship and other rights are tied - worth fighting for? Is monogamy, even egalitarian monogamy, obvious? Tractate Sotah fights for marriage - albeit in asymmetrical patriarchal ways - but what of consensual non-monogamy? What if we deviate beyond the strictures of man/woman with its inevitable hierarchical violences, cuts, and erasures and allow more than these two possibilities? What if we center more-than-binary thinking, and engage in it prior to the man/woman dualism instead of considering the duo and its inevitable pairing as something prior and obvious from which we (as good liberals) kindly allow queer and trans people to unenlist? How does the seeming inevitability of binary sexgender - man and woman, or let’s just call it patriarchy - all too easily underpin taken-for-granted and unimaginative kinship arrangements (“family”) or even unjust communal configurations along the lines of race and nation? How do we deviate from these? What unthinkable, pre-erased ways of radical living, loving, community, and kinship can we summon for ourselves?

Wednesday, October 19, 2022 at 7 PM

〰️

Wednesday, October 19, 2022 at 7 PM 〰️