Exodus of Language

The Silent Story Behind Morphing Glyphs

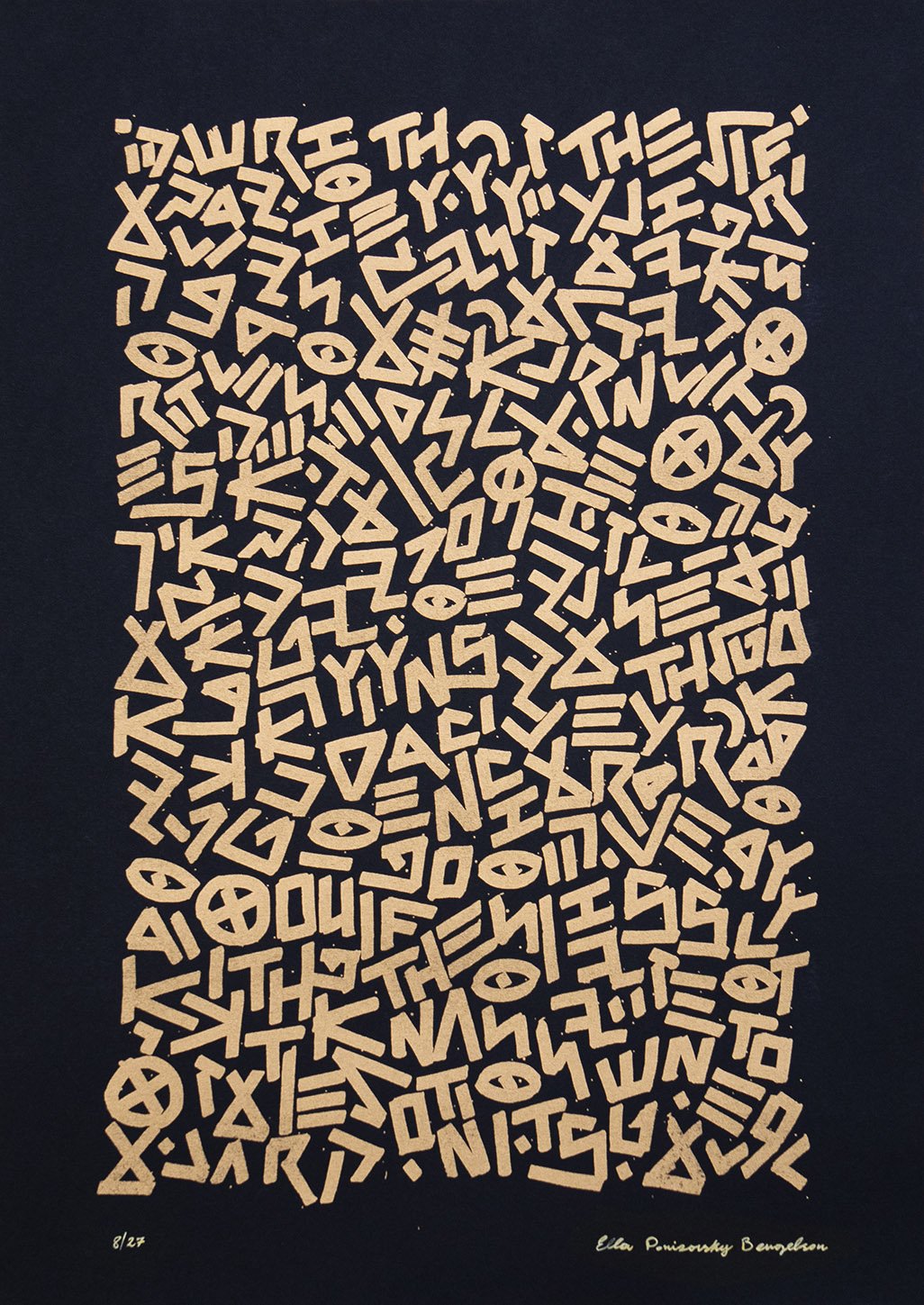

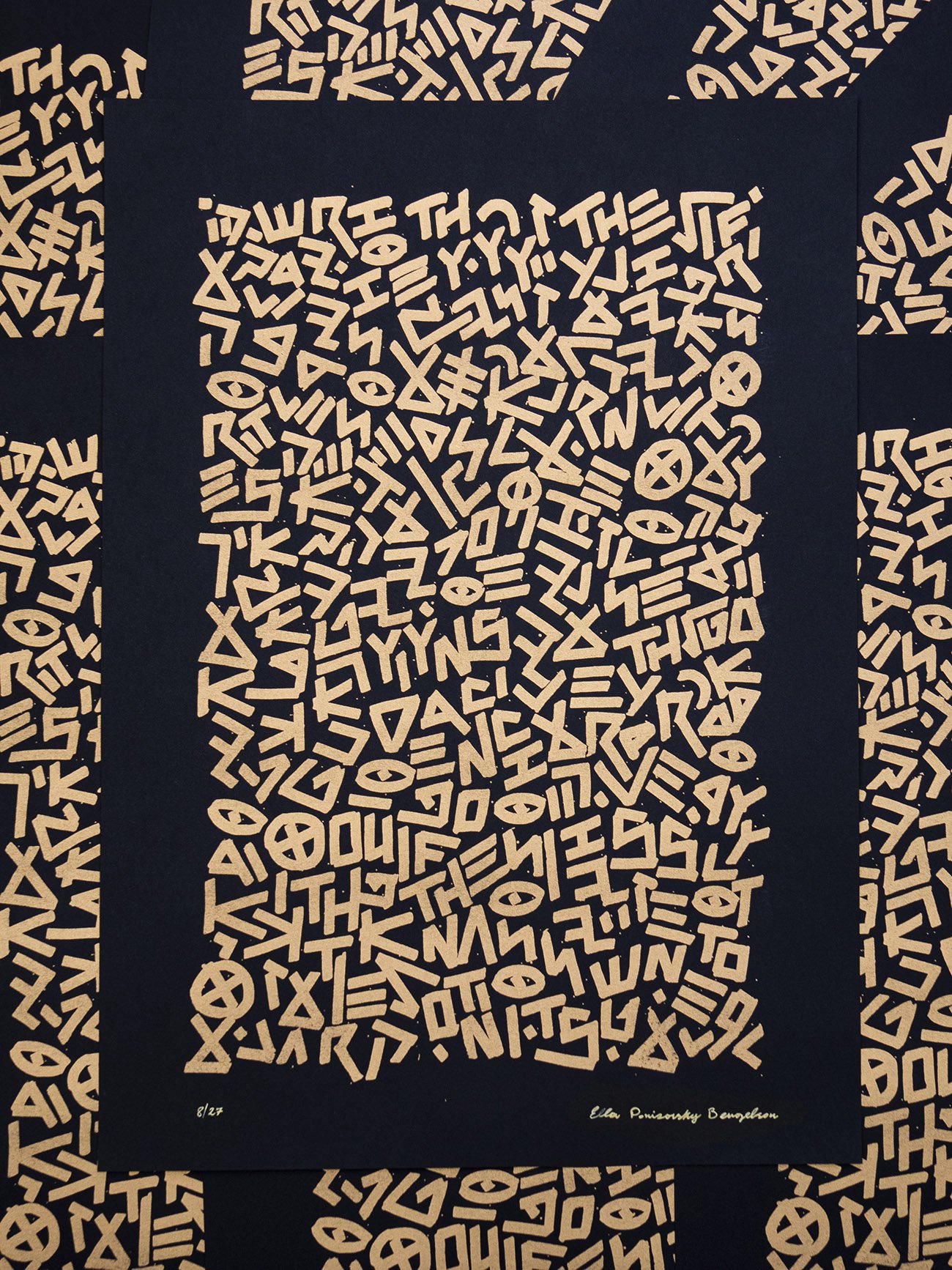

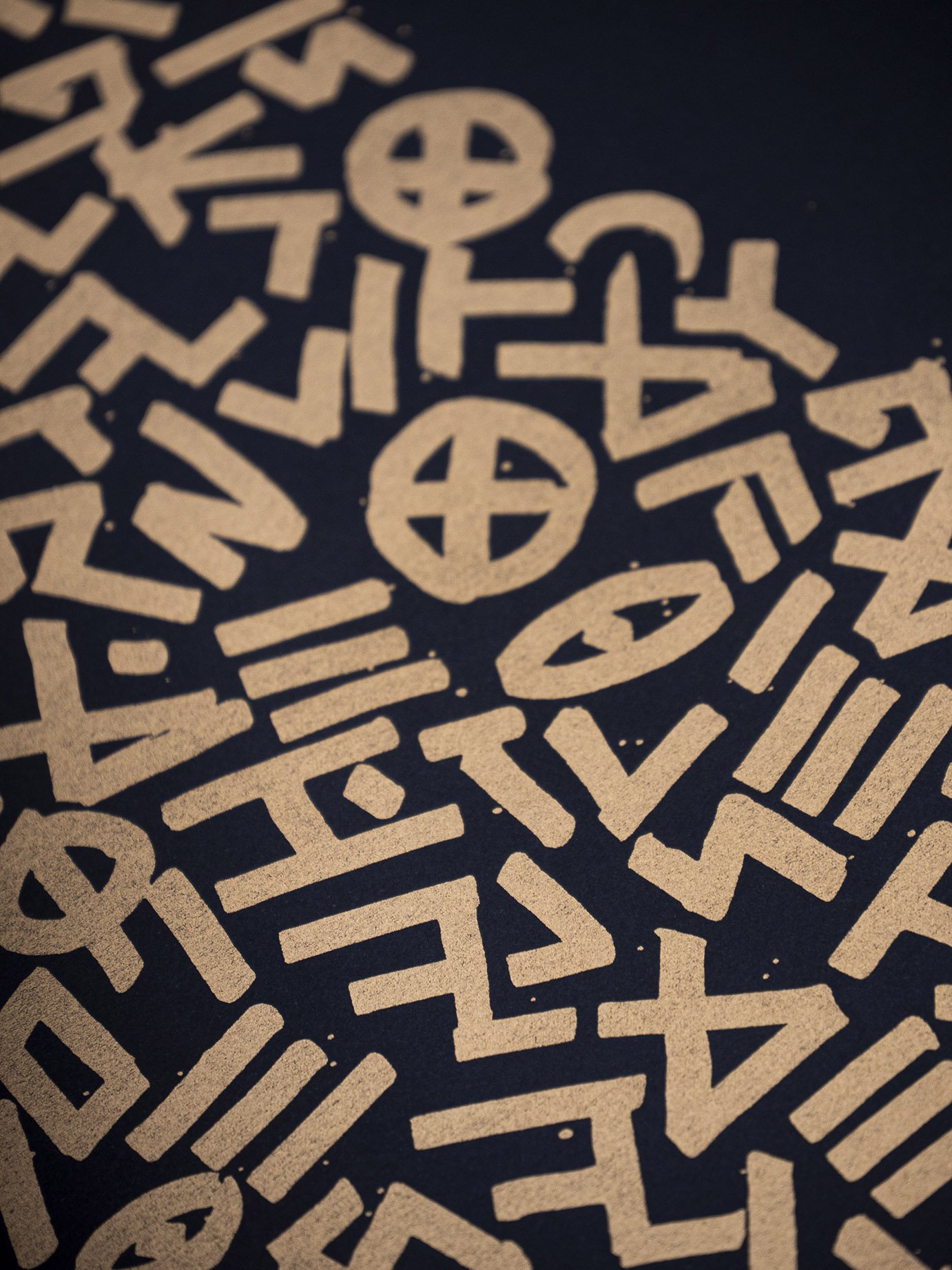

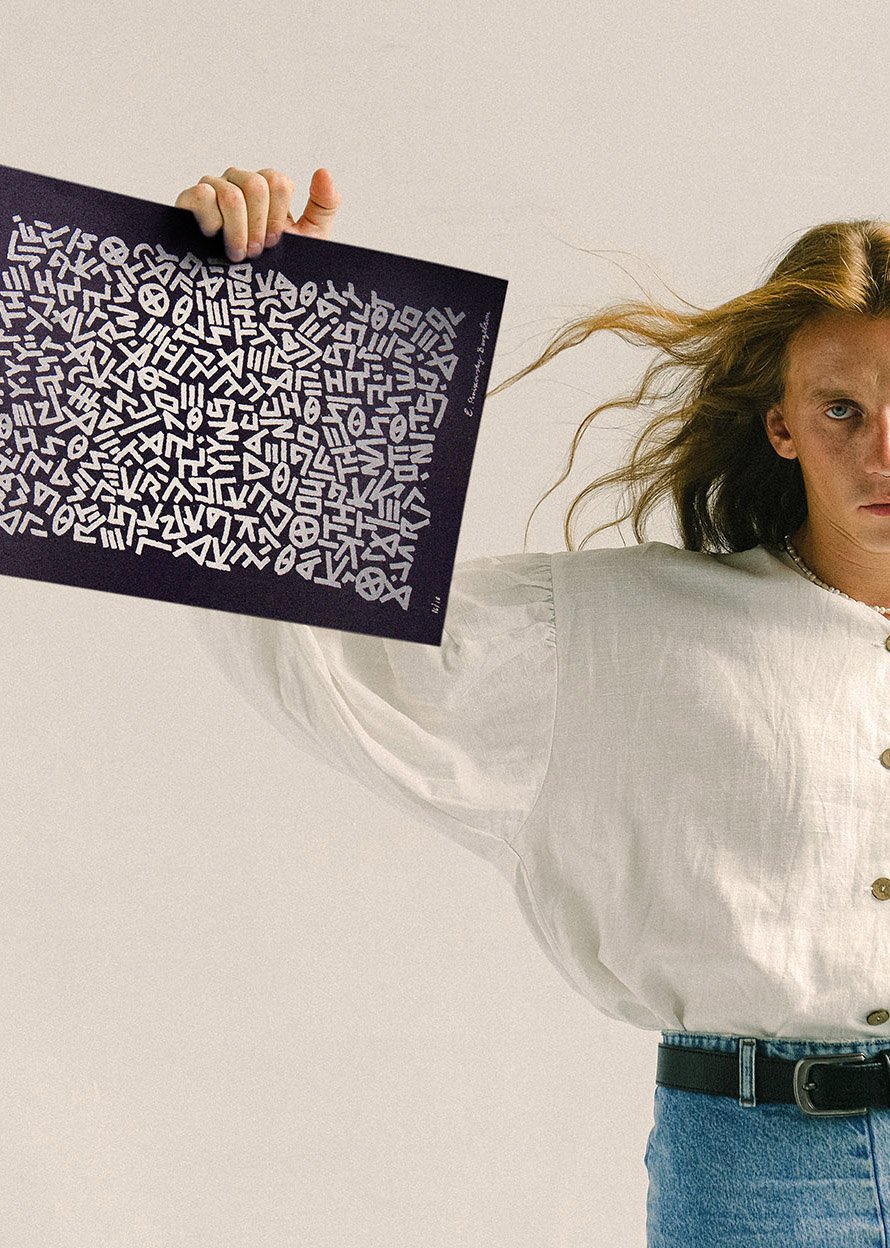

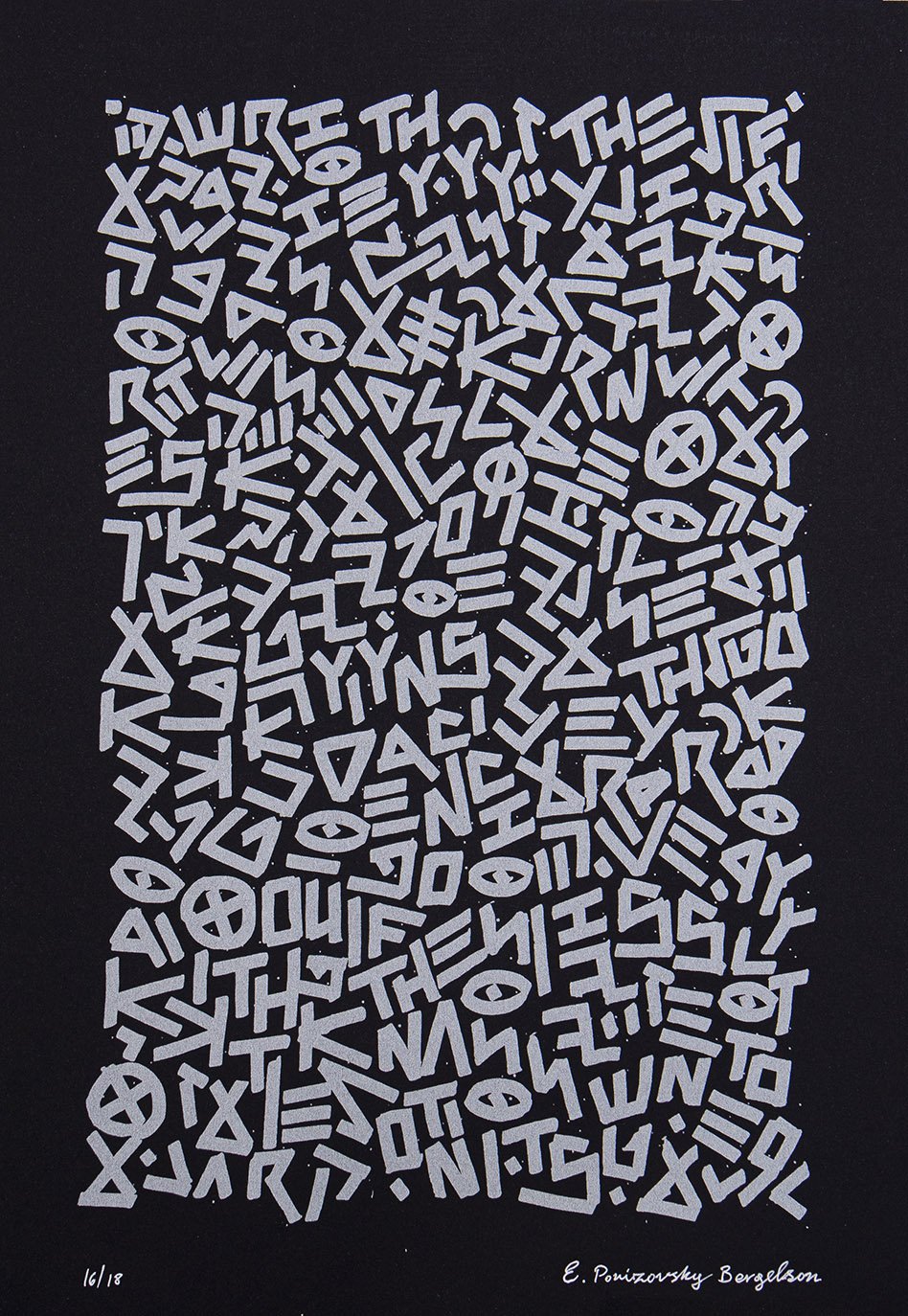

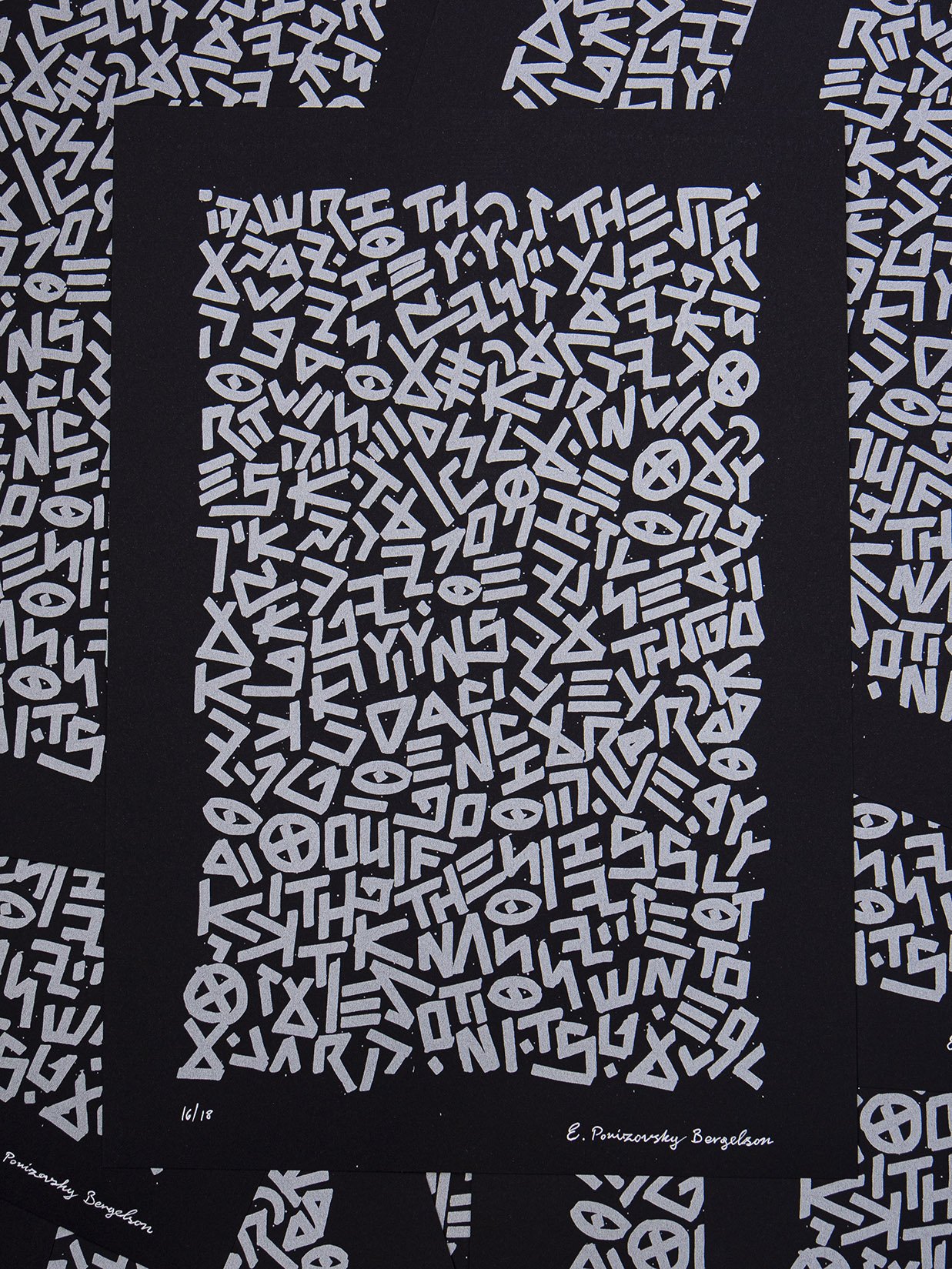

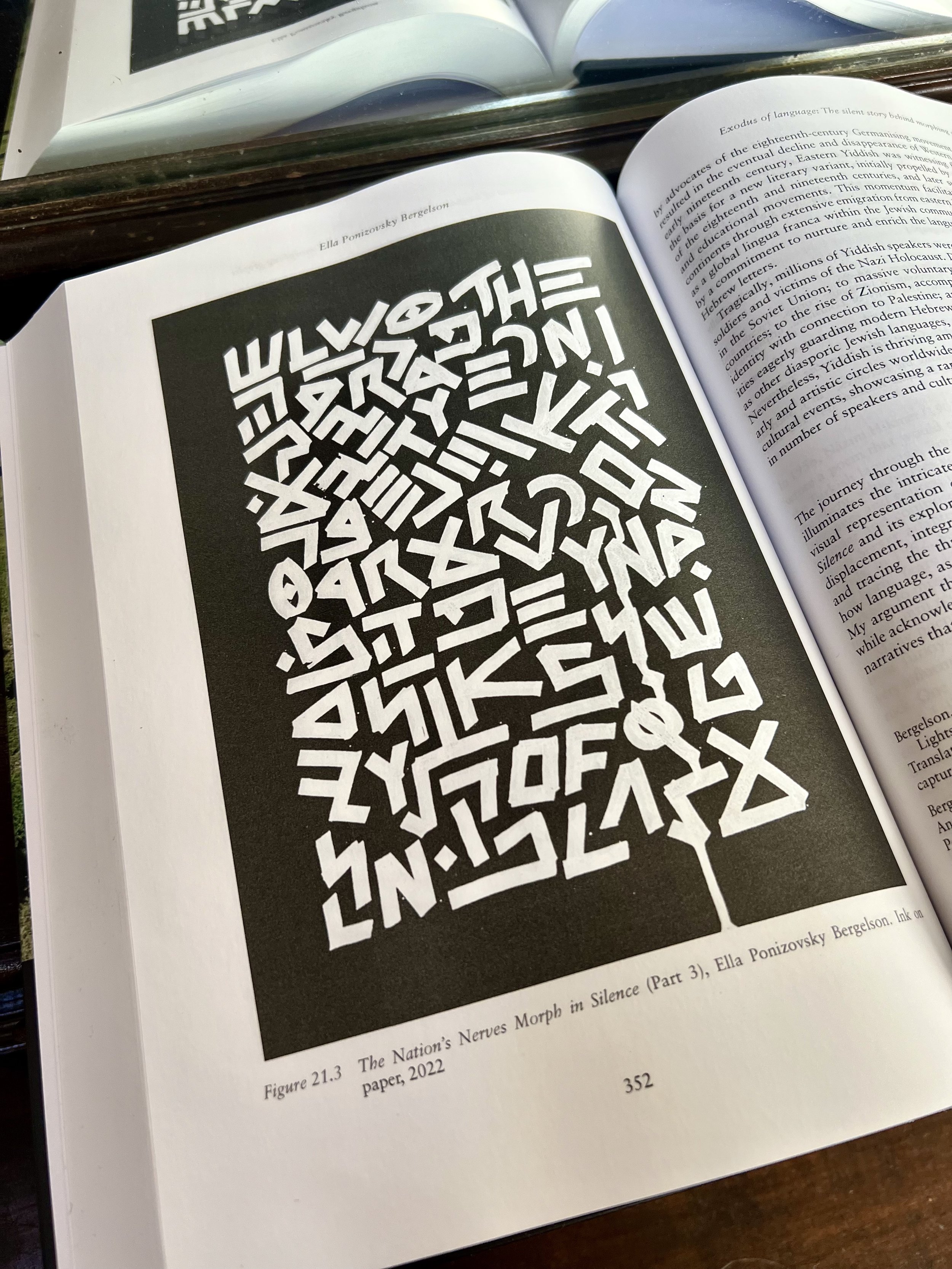

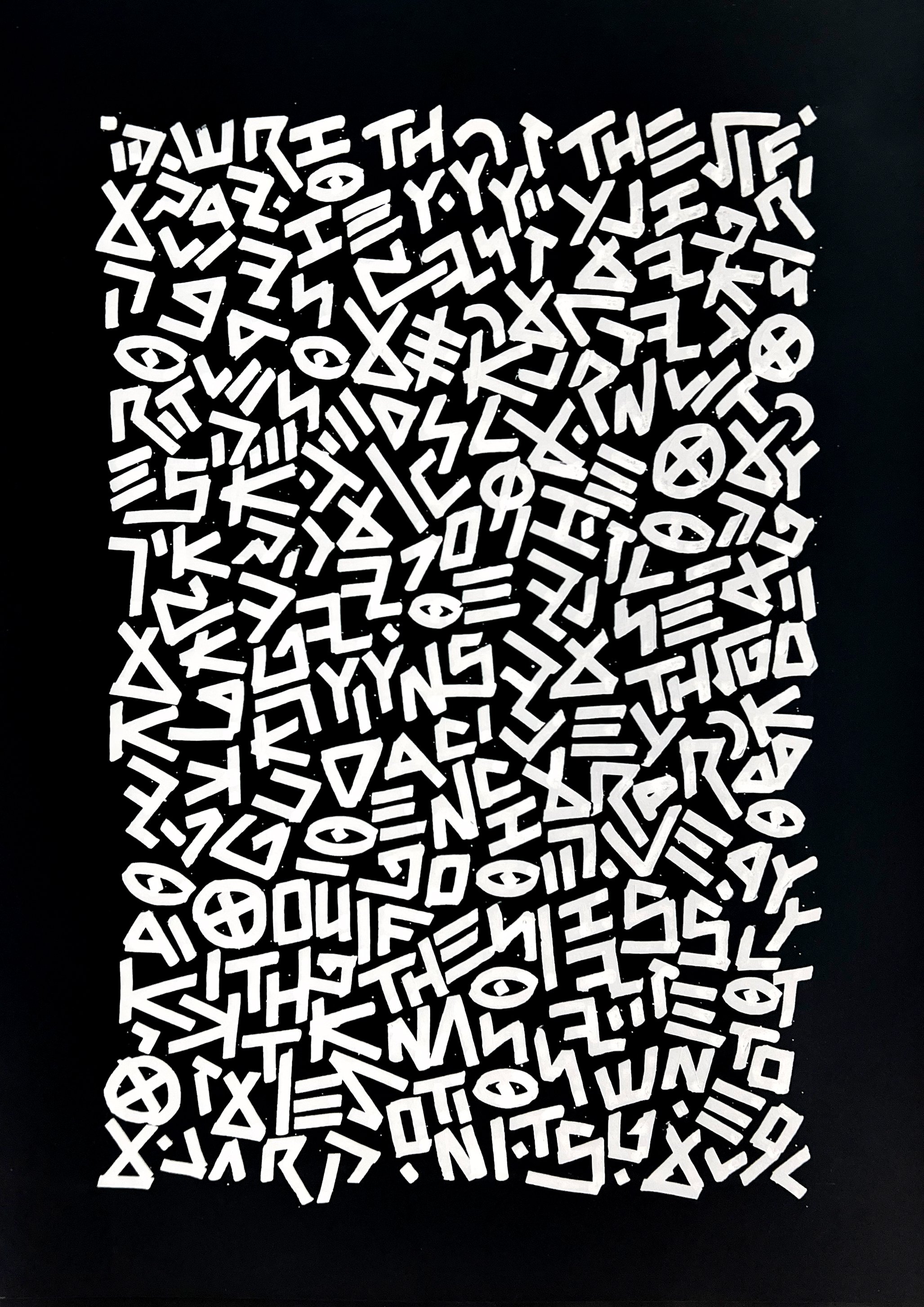

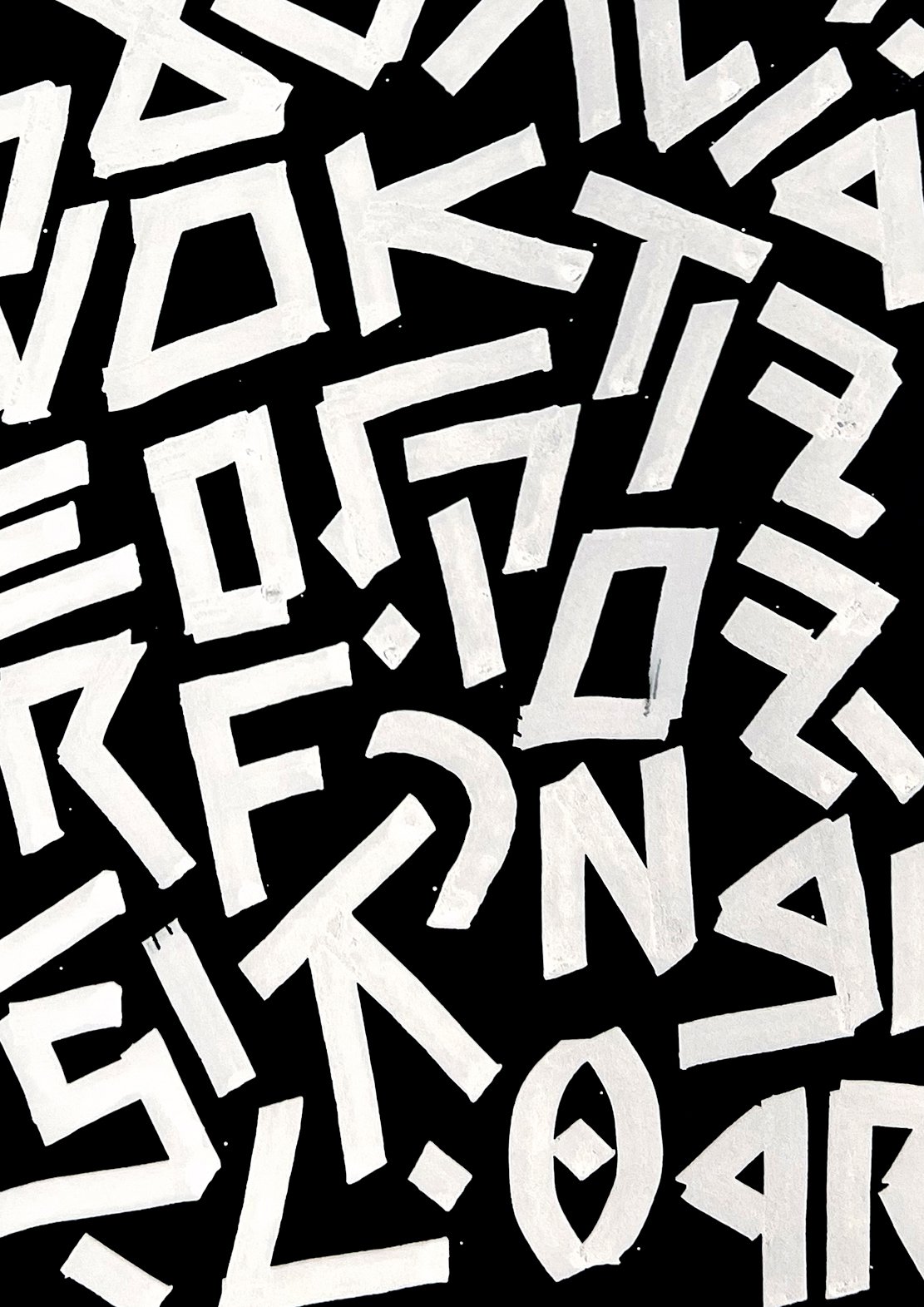

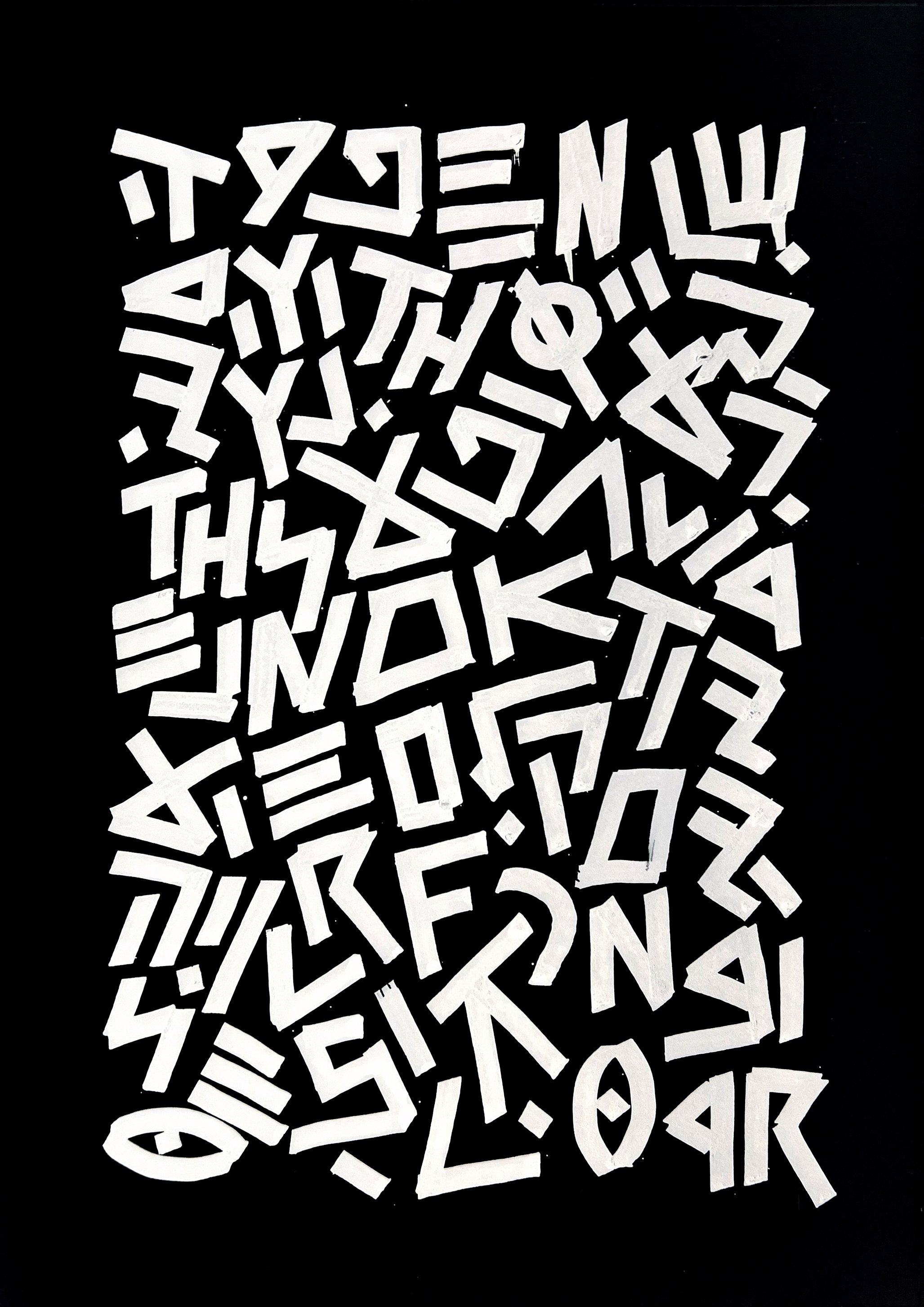

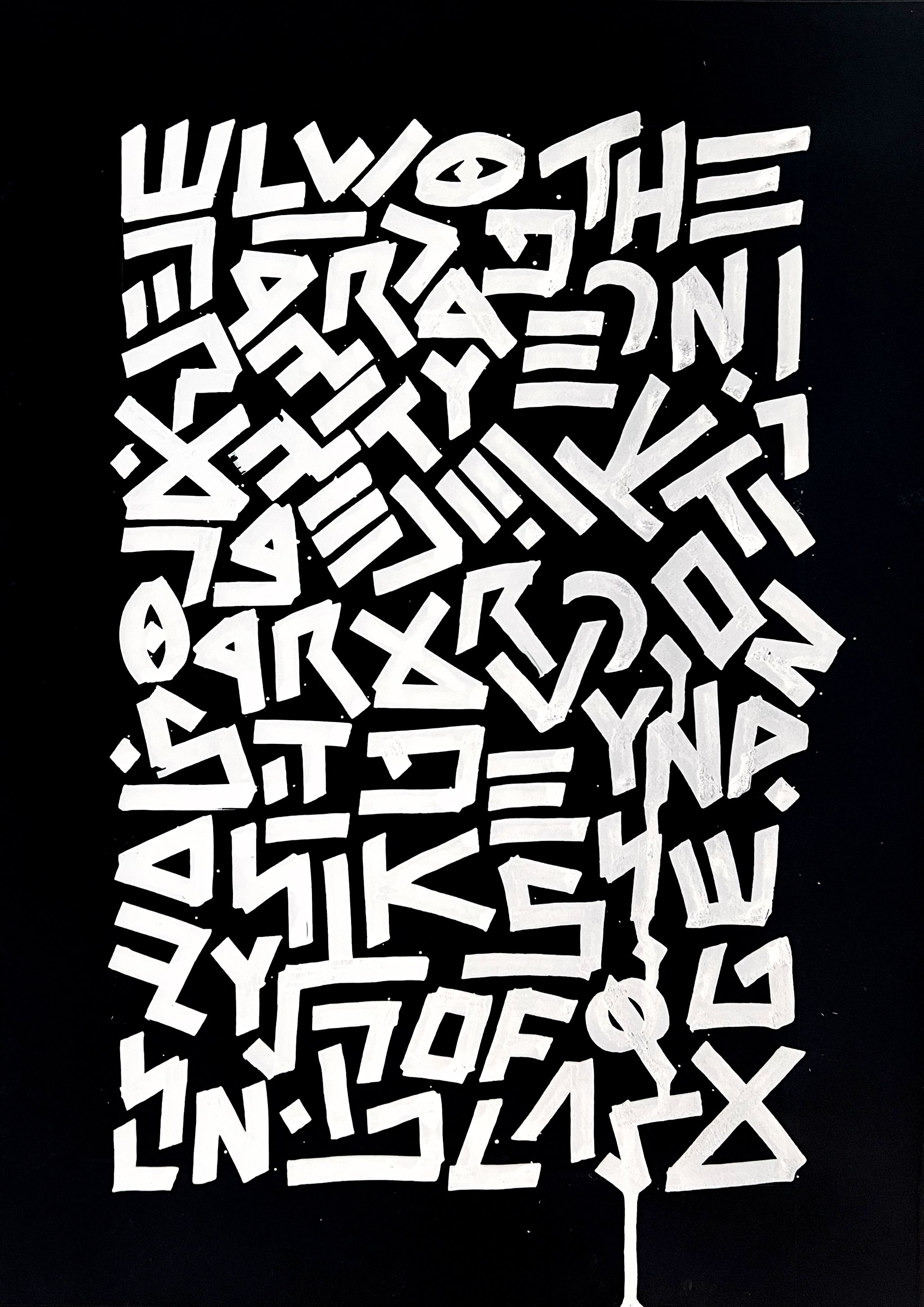

There is a silent story behind morphing glyphs. The letterforms as visual elements, and their interconnectedness, offer contemplation on their origins, amalgamation, and evolution. The image is an element in a five-part artwork that was created as a contribution to the scholarly journal published in fall 2024: "The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Migration." Accompanying the works is an article that delves into the migration and integration of typography. The extinction of languages and alphabets is examined in the context of imperial power dynamics. Central is the evolution of Hebrew typography and the external influences involved in it, such as geopolitical shifts and exile. Which comprehensions can be retrieved while tracing origins of glyphs and their symbolism, delving into the depths of history of writing systems?

Published at The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Migration, 2024

Limited Edition

〰️ 2023 〰️

Limited Edition 〰️ 2023 〰️

High quality Riso prints on Fine Paper

〰️

High quality Riso prints on Fine Paper 〰️

Ink on paper, replicated in a limited edition Riso prints on fine black paper.

Numbered & Signed.

Gold, Black; A2 (420 x 594 mm / 16.5 x 23.4 inches). 27 copies

Silver, black; A3 (297 x 420 mm / 11.7 x 16.5 inches). 18 copies

The revenues will be allocated to the production of new artistic endeavors in public spaces.

Thank you for your support!

Exodus of Language

The Silent Story Behind Morphing Glyphs

Abstract

The journey through the evolution of language and typography presented in this chapter illuminates the intricate interplay between cultural migration, power dynamics and the visual representation of communication. The artwork The Nation’s Nerves Morph in Silence and its exploration of Hebrew typography encapsulate the poignant narratives of displacement, integration and the struggle for cultural preservation. By delving into the past and tracing the threads of linguistic transformation, we gain a deeper understanding of how language, as a mirror of society, adapts and evolves in response to historical forces. This chapter underscores the significance of embracing our linguistic heritage while acknowledging the impermanence of cultural forms, urging us to reflect on the shared narratives that shape our identities and connect us across time and space.

This chapter discusses the significance of language and typography as cultural elements and explores the visual representation of language migration and integration. My artwork, titled The Nation’s Nerves Morph in Silence, anchors itself in the evolution of Hebrew typography and its external influences, such as imperialism and exile, as a reflection of displacement, integration and power dynamics.

The artwork employs the Yiddish story “Among Refugees” written by Dovid Bergelson, my great-grandfather, which explores the existential crisis and fear of losing cultural and linguistic connections experienced by a displaced writer. The chapter also delves into the history of writing systems, tracing the origins of alphabets and their symbolic meanings. The evolution of languages and alphabets is examined in the context of power shifts, imperialism and colonisation. Using letterforms as visual elements, the artwork within the chapter seeks to convey messages and symbols that transcend words and reflect on cultural roots, their integration and transformation.

Cultural Migration

Language and the study of letterforms – termed typography – are defining elements of a culture. By using strict sets of rules, they indicate the nature of it, both in content and in visual form. Having had to relocate to a new continent twice thus far, as cultural hybridity became my self-definition, exploring and contemplating manifestations of migration and integration processes through visualisation of language came to be the centre of my creative motivation.

Typography is the intricate craft of orchestrating alphabetic symbols, a cornerstone of visual communication. It contemplates the historical trajectory of scripts, moulded by human exigencies and technological evolutions. This multidisciplinary realm envelops societal, linguistic, psychological and aesthetic dimensions. Letterforms, as representors of sounds, transmit narratives to observers, relying on their legibility and comprehension. Primarily, typography is an endeavour to capture the spectator’s gaze, instigating an optimal understanding. Ultimately, it functions as the conduit for information exchange between the author and the reader. Designer and scholar Haken Ertep writes: “Typography is the main means of expression for those who intend to create a visual representation consisting of the elements of writing […] Typography has a very fundamental and contemporary place in everybody’s world” (Ertep 2011: 45).

As cultural spaces are influenced by migratory waves and international relation shifts, so the language and its visual representation – typography – are also morphing. In my own work, my intention is to create an interpretation of this process that reflects on the characteristics of geopolitical waves, past and present. By undertaking forms of language visualisation to reflect on historical political shifts, in the shadow of today’s reality of violence – evoked by the rise of nationalism, borders and system control – absolute perceptions can be critiqued and questions can be raised. My current visual interpretation is designed to expose the entanglements and intertwinings of cultures and ideologies, refuting the claim for a uniform national existence and exposing the organic and anarchist attributes of both language and typography formation, contradicting the claim of their qualification as univocal cultural elements. The five-part piece addresses the development and evolution of the Hebrew typography from Paleo-Hebrew, through Aramaic to the modern Hebrew alphabet, focusing on external influences such as conquest and forced translocation. It compares that path to more recent forms of letters, thus reflecting on overall displacement, integration and cultural positions of power.

A Writer's Exile

The Nation’s Nerves Morph in Silence is derived from an early twentieth-century Yiddish story. It transcodes a paragraph of the story “Among Refugees,” written in Berlin in 1922 by the Yiddish writer Dovid Bergelson (1884–1952), my great-grandfather, who lived and worked in the city during the 1920s.

Dovid Bergelson, who is considered one of the leading Yiddish writers of his time, was already a well-known expressionist writer when he was part of a migration wave that included numerous authors, poets, artists and scholars who settled in Berlin at a time of excitement, as literature and art flourished, if all-too-briefly, in the European metropolis. A selection of his Berlin stories reappeared in English as The Shadows of Berlin in 2005, published by the iconic publishing house City Lights Books in San Francisco. In these stories, life in Berlin is captured at the precarious moment between world wars – in particular, the writing follows the uneasy existence of intellectual exiles in the rapidly growing metropolis. The stories offer unique glimpses into a community and a world now lost (Neugroschel 2005).

Of all Bergelson’s stories set in Berlin, “Among Refugees” is the most prominent and has received critical attention. It offers a study of different forms of existential crisis, precipitated by exile. In brief, the story is about a well-established Yiddish writer who is visited by a strange young man who introduces himself as a Jewish terrorist. He shares with the narrator his life story, which is marked by relocations. He admits to being a writer himself, while blending in his own life story and another fictional story he had composed. The purpose of his visit is the search for a weapon, which he needs to fulfil his longing to assassinate his neighbour, a pogromist, who organised a massacre and is responsible for the murder of the young man’s family in Ukraine. This resolution amounts to a suicide. In his suicide letter, the young writer explains: “I understand everything now: I’m a refugee among refugees. I don’t want to be one anymore” (Bergelson 1922/2005).

Within the narrative, the author overlays his personal anxieties upon the protagonist, specifically the looming fear of devolving from his esteemed stature as an accomplished writer to the realm of a deranged wanderer. This allegorical portrayal eloquently encapsulates the writer’s preoccupation with losing his culture and language, as the connection to his readership fades. The narrative serves as a testament to the writer’s internal struggle, veiling beneath its surface the author’s apprehensions regarding his absent readership:

Lurking is Bergelson’s own dread, projected onto his protagonist, of one day slipping from his hard-won status as a successful professional author to the level of a mad vagabond who creates stories that he foolishly believes to be useful to people. Above all else, the suicide of the young man in the story is the artistic suicide of a writer who realises that his language no longer serves him, that his works are no longer read, he has been left isolated and alone. (Senderovich 2007)

That concern is being subtly disintegrated in “Among Refugees,” as the perspective unveils how Berlin-based Yiddish artists, poets and authors were confronted with the old identity versus the new, fast-changing modernist art world, in search for their future readers. Using a virtuosic writing style, in the form of three stories woven into each other, Bergelson’s work exposes that conflict with its complexities. The reader in Berlin appears unrecognisable to the author when contrasted with the readers in his homeland. In a foreign milieu, the established conduits connecting writer and reader degrade, culminating in the author’s creation losing its relevance for the reader. The once familiar and understanding reader diminishes into obscurity. “Among Refugees” unveils Bergelson’s Berlin as a realm of uncertainty, where the customary avenues of engagement among displaced individuals – and between displaced writers and readers – dissolve.

Bergelson’s existential concerns are eventually resolved by concluding that the ultimate Yiddish reader exists in the Soviet Union, as Bergelson declares in his article “Dray Tsentern” (Three Centers; Bergelson 1926). This declaration was acted upon only years later, in 1934, as he was the last of his associates to leave Berlin and relocate to Moscow. There, ultimately, after two decades of fruitful cultural and political activity, Bergelson and his colleagues were falsely charged with treason and espionage during an antisemitic campaign against “The Rootless Cosmopolitans,” due to their involvement in the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and were ultimately sentenced to death in a staged trial (1952). This event, which has become known as “The Night of The Murdered Poets,” was discovered by the public only until after Stalin's death in 1953, and caused the progressive Yiddish cultural community in the Soviet Union to dramatically fade. In August 2022, their deaths were commemorated for the 70th time.

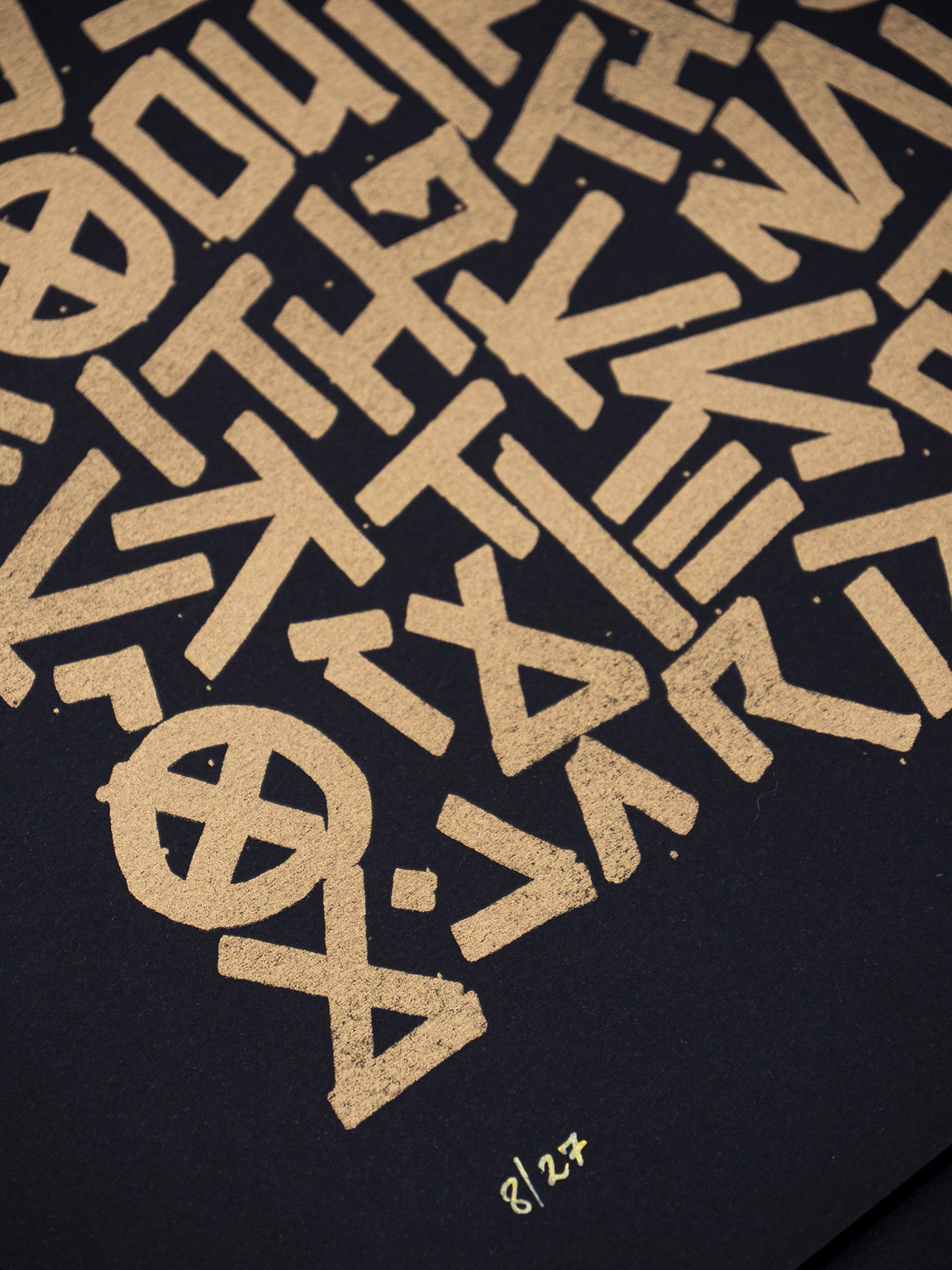

My piece combines Yiddish, English and Paleo-Hebrew. These are chosen to represent different times in the evolution of writing, as well as variances of the influence exercised by displacement on language and its visual manifestation. Moreover, the piece suggests the visible connection between these three codes. The action of transcoding a century-old Yiddish text to an almost-extinct alphabet and urging the reader to decipher it may carry a statement not on the position of Yiddish literature alone, but also on other extinct indigenous dialects and typography systems, in the contemporary cultural reality. By regressing to the primary and elementary, the piece addresses both influences such as exile and displacement and the act of communion with ancestors. As in the original text, at the core of the piece lies the attempt to integrate the inner conflict between an old identity and a new culture, the struggle for integration while preserving one’s cultural roots.

The singled-out paragraph, which repeats in my five-part piece in linear and nonlinear forms, reads:

“Writers, I thought, were the conscience of the nation. They are its nerves. They present their nation to the world. People read a writer’s works because they want to learn how the nation lived at his time. And so I’ve come to you. I’ve told you everything. And now that I’ve told you everything, you are responsible as I am and even more because you are a writer."

Bergelson, 1922

The Spring of Letterforms

The utilisation of letters and words as visual representations of broader ideas and emotions in my artwork finds justification in its connection to the origins of written communication. Writing initially began as drawings that carried messages and narratives. Drawings found on cave walls were the earliest forms of visually conveyed messages, predating direct face-to-face communication. Looking back at the evolution of the letters printed on this very page, this transformative journey can be comprehended.

An alphabet consists of characters with phonetic values, arranged to form words in a phonographic system where characters represent sounds. When letters are placed together, they create words describing objects, actions or ideas. Combined words form sentences or paragraphs that elaborate on content and concepts – unlike ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian writing, where each word had a pictogram representing the whole word, later recognising that these pictograms could stand for the sound of the first letter. Around 1500 bce, the process of assigning phonetic values to hieroglyphs commenced.

The reconstruction of the history of the Semitic letter Aleph (A) is an example of that process; in biblical Hebrew the word Aleph means ox. The original pictograph for this letter is a simplified illustration of an ox head, representing strength and power due to the work performed by the animal in the field. Accordingly, this pictograph represented a ruler or leader. The name of the letter, Aleph, corresponds to the Greek Alpha and the Arabic Aliph. Its root is adopted from the parent root El, meaning strength and power and is the probable original name of the pictograph. The letter Lamed (L) is a shepherd’s staff and represents authority. The combination of these two pictographs means strong authority. Many Near Eastern cultures worshipped the god El, which appeared as an ox in carvings and statues. The word El is commonly used in the Hebrew Bible for God. The tribes of Israel chose the form of a calf as an image of God at Mount Sinai, showing their association between the word El and an ox.

The concept of the ox and the shepherd’s staff in the word El have persisted into modernity as the sceptre and crown of a monarch, the leader of a nation. These objects are representative of the shepherd’s staff, an ancient sign of authority, and the horns of the ox, an ancient sign of strength. The Early Semitic pictograph of Aleph was simplified in the Middle Hebrew script and continued to evolve in the Late Hebrew and the modern Hebrew. The Middle Semitic was adopted by the Greeks to become the letter Alpha and carried over into the Roman A. The Middle Semitic A became the number 1 that is used today.

The process of associating distinct sounds with glyphs advanced until a curated set of 22 pictographs was meticulously chosen to represent fundamental phonetic elements within spoken language. The earliest manifestations of this innovative alphabetical script emerged within the area of Palestine, denoted as Phoenicia or Canaan in scriptural texts. This script is sporadically referred to as Paleo-Hebrew (ancient Hebrew) and Ugaritic, adopting the nomenclature of the Canaanite city where its inaugural form was excavated.

This newfound script’s elemental nature brought about a transformative shift in written communication, marking a pivotal juncture where a mere handful of symbols became sufficient to convey narratives or conceptual nuances. This pivotal departure from the extensive array of intricate pictograms, which demanded substantial effort to learn, inscribe and decipher, was momentous. The progressive trajectory of this innovative alphabet swiftly garnered favour, proliferating across the expanses of the Middle East and the Mediterranean region. This diffusion yielded consequential outcomes, culminating in the evolution of the Semitic, Greek and Roman alphabets – integral foundations of the contemporary alphabetic frameworks employed in present times (Blum 2017).

To conclude, every individual letter encapsulates a narrative and a unique perspective on the world. Delving into the historical evolution of letterforms provides a fascinating window into the experiences of our forebears. Within my artwork, the amalgamation of these letter combinations transcends mere linguistic constructs; each letter serves as a cryptic code, a potent symbol with the potential to be unravelled.

The Fall of the Primary

The extinction processes of languages and alphabets, globally, are reflecting on histories of power-balance shifts, imperialism and colonisation. By tracing back the eradication history and development of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet these can be observed.

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet closely resembled in design and structure the Phoenician script, initially believed to have originated from the Phoenician civilisation, based on archaeological evidence. The alphabet dates back to the tenth century bce, evolving from the Proto-Canaanite script of the Late Bronze Age in Canaan. It became the primary writing system for the Hebrew language among the Israelites in the biblical regions.

This alphabet simplified writing by using fewer symbols to convey ideas effectively. However, around the sixth century bce, during the Babylonian exile following the Second Temple’s destruction, it yielded to the imperial Aramaic alphabet, precursor to the present Hebrew Square-Script. The Samaritans, who remained in Israel and number fewer than a thousand today, have preserved the use of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet from ancient times.

The decline and eventual disappearance of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet can be seen as a reflection of historical, current and impending authoritative supremacy dynamics. The widespread influence of Aramaic, spanning the Assyrian and Persian Empires, significantly shaped the trajectory of Semitic languages. During their period of Babylonian captivity, Jewish scribes (Sofrim) played a pivotal role in the evolution of the Hebrew alphabet, incorporating an Aramaic influence referred to as Ashura.

This adaptation was prompted by their recognition of the fluidity and ease offered by the Aramaic writing style, a departure from the rigid nature of Paleo-Hebrew characters. The Assyrian script emerged as a synthesis of Paleo-Hebrew and Aramaic letterforms, achieving a delicate equilibrium in terms of line contrast and linear composition. The adoption of the square, block-scripting style introduced a smoother, swifter writing experience and enhanced legibility. This style gained prominence in the writing of numerous Judaic texts during the period of exile and beyond. Gradually, this script became the predominant form of Hebrew alphabetic writing.

My visual interpretation involves a fusion of diverse languages and alphabets: Paleo-Hebrew, Yiddish (the modern Hebrew alphabet) and English. Its purpose is to visually signify the close proximity of these distinct alphabets and to blur the divisions among them. Furthermore, it aims to diminish the hierarchical distinctions between them by disregarding and challenging the conventional binary structure of writing, wherein words conform to standard, linear arrangements. Within this composition, the letters engage in a dialogue with one another, adapting to each other’s forms, positions and angles. Rather than adhering to rigid binary patterns, the letters meander in a distinctive manner influenced by their individual characteristics and shapes, in a behaviour that stands as a resistance to simplistic binary world views.

Yiddish - Manifestation of Hybridity

In the wake of the dispersion of the Jewish population and destruction of their Second Temple, the Hebrew language and its typography found enduring relevance in religious contexts. This pivotal juncture imbued the act of writing with renewed significance. Confronted with the absence of a tangible place of worship, the Jewish community hurried to transcribe their oral traditions and rituals, safeguarding them against gradual erosion. This earnest endeavour yielded a momentous outcome: the creation of the Talmud, a seminal Rabbinic literary work. Hebrew, primarily employed for prayer and the recitation of religious texts, assumed heightened prominence. Notably, while Jewish scholars and intellectuals maintained fluency in spoken Hebrew, alternative written forms emerged to articulate the evolving Jewish languages, utilising local alphabetic conventions. Amid the diaspora, Hebrew retained its sacred status within the Jewish populace, co-existing with a hybrid dialect melding Hebrew and the language of their surroundings. Yiddish, in Central and Eastern Europe, blended German and Hebrew, epitomising regional cultural synthesis.

Yiddish, a unique Germanic language, defied convention with its use of the Hebrew alphabet. By the nineteenth century, it had become widespread across countries with Jewish populations. Alongside Hebrew and Aramaic, it is a significant literary language in Jewish history, originating in the ninth century with the rise of Ashkenazi culture in central Europe. Its origins blend two linguistic sources: a Semitic component, including post-classical Hebrew and Aramaic from the Middle East, and a dominant Germanic component from various German dialects. Starting in German-speaking regions, Yiddish spread to eastern Europe, absorbing elements of Slavic languages. Its hybrid nature, its diverse roots, make it an instrument for grasping exile reality.

Since its inception, Yiddish has served as the language of both everyday life and scholarly Talmudic institutions. Its literary corpus has steadily expanded through the centuries, particularly in genres not traditionally covered by Hebrew and Aramaic. The emergence of Yiddish printing in the sixteenth century acted as a catalyst, leading to the establishment of a standardised literary form based on Western Yiddish conventions. The gradual assimilation of Yiddish into the German linguistic sphere, coupled with a concerted effort by advocates of the eighteenth-century Germanising movement to suppress the language, resulted in the eventual decline and disappearance of Western Yiddish. In contrast, by the early nineteenth century, Eastern Yiddish was witnessing flourishing growth. It formed the basis for a new literary variant, initially propelled by the mystical Hasidic movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and later supported by other sociopolitical and educational movements. This momentum facilitated Yiddish’s dispersion across the continents through extensive emigration from eastern Europe, preserving its traditional role as a global lingua franca within the Jewish community. The Yiddishist movement, driven by a commitment to nurture and enrich the language, was fortified by the proliferation of Hebrew letters.

Tragically, millions of Yiddish speakers were victims of World War II, both as Red Army soldiers and victims of the Nazi Holocaust. Due to the official suppression of the language in the Soviet Union; to massive voluntary shifts to other primary languages in western countries; to the rise of Zionism, accompanied by its campaign to promote a new Jewish identity with connection to Palestine; and then to the antagonism of early Israeli authorities eagerly guarding modern Hebrew and making an acute effort to ban Yiddish as well as other diasporic Jewish languages, the number of Yiddish speakers was further reduced. Nevertheless, Yiddish is thriving among ultra-Orthodox communities and reviving in scholarly and artistic circles worldwide. This resurgence is marked by research, translation and cultural events, showcasing a rare case of an almost-extinct language experiencing growth in number of speakers and cultural relevance.

In Essence

The journey through the evolution of language and typography presented in this chapter illuminates the intricate interplay between cultural migration, power dynamics and the visual representation of communication. The artwork The Nation’s Nerves Morph in Silence and its exploration of Hebrew typography encapsulate the poignant narratives of displacement, integration and struggle for cultural preservation. By delving into the past and tracing the threads of linguistic transformation, we gain a deeper understanding of how language, as a mirror of society, adapts and evolves in response to historical forces. My argument therefore underscores the significance of embracing our linguistic heritage while acknowledging the impermanence of cultural forms, urging us to reflect on the shared narratives that shape our identities and connect us across time and space.

****

Further Reading

Bergelson, D. (1922/2005). “Among Refugees.” The Shadows of Berlin. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Translation from Yiddish to English, by Joachim Neugroschel; a short fictional story set in Berlin that captures the precarious moment between world wars, in particular the crises of an author in exile.

Bergelson, D. (1926). “Dray Tsentern” (Three Centers). In shpan, 1, 84–96.

An essay expressing a belief that the Soviet Union had eclipsed the assimilationist USA and backward Poland as the great future locus of Yiddish literature.

Senderovich, S. (2007). “In Search of Readership: Bergelson among the Refugees.” In J. Sherman and G. Estraikh (eds.), David Bergelson: From Modernism to Socialist Realism (pp. 150–166). London: Legenda.

The chapter explores the self-creation and transformation of writer David Bergelson within the emigrant Yiddish literary scene in Weimar Berlin.

Blum, S.T. (2017). “Hebrew Typography: A Modern Progression of Language Forms.” Faculty and Staff Publications. XULA Digital Commons 47. Xavier University of Louisiana.

The article examines the development of Hebrew typography within the context of the Hebrew language revival influenced by Haskalah and later Zionist movements, focusing on its significance in defining Jewish identity and nationalism in the twentieth century.

Bibliography

Bergelson, D. (2005). The Shadows of Berlin, San Francisco: City Lights Books. (Originally published 1922.)

Bergelson, D. (1926). “Dray Tsentern” (Three Centers). In shpan, 1, 84–96.

Blum, S.T. (2017). “Hebrew Typography: A Modern Progression of Language Forms.” Faculty and Staff Publications. XULA Digital Commons 47. Xavier University of Louisiana.

Ertep, H. (2011). “Typography as a Form of Cultural Representation.” The International Journal of the Arts in Society: Annual Review, 6(3), 45–56.

Neugroschel, J. (ed.). (2005). Radiant Days, Haunted Nights: Great Tales from the Treasury of Yiddish Folk Literature. New York: Overlook Duckworth.

Senderovich, S. (2007). “In Search of Readership: Bergelson among the Refugees.” In J. Sherman and G. Estraikh (eds.), David Bergelson: From Modernism to Socialist Realism (150–166). London: Legenda.